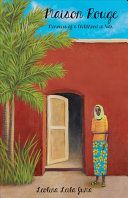

Maison Rouge: Memories of A Childhood in War

Maison Rouge

Maison Rouge

Young Adult Nonfiction

Tradewind

March 15, 2020

118

Leila was 16 years old when her family home in the Democratic Republic of the Congo was destroyed by rebel soldiers. In this gut-wrenching memoir, she gives an account of her life before and after her family was torn apart by the twin nightmares of civil war and invasion. Maison Rouge is a story of war and unspeakable loss. It is also the story of survival. Eventually, through the United Nations refugee program, Leila and her family were finally able to relocate to Canada. Publisher

In her “memories of a childhood in war,” author Liliane Leila Juma takes readers back to her joyous life in Uvira, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), before a perfect storm of war, wanton violence and famine hit her town. “I was living happily” (16), she remembers. Hers was a plush neighborhood of Uvira, a town located on the Congolese side of the Rift Valley of the Great Lakes Region, in the South Kivu Province, near the border with Burundi. In “Maison Rouge,” as her luxurious mansion was fondly nicknamed, Leolina enjoyed a life of affluence maintained by “housekeepers, cooks, tutors, nannies and seamstresses” (17). Although her family was Muslim, she attended a diverse Catholic school that catered to the children of opulent expatriate and upper-class Congolese families. In the early 1990s, ethnic strife simmered in the Great Lakes Region and flared up at times, when, for instance, in October 1993, war broke out in Burundi and sent thousands of refugees across the border and into Uvira. Then, in April 1994, all hell broke loose when the aftermaths of the genocide in Rwanda spilled over Congo’s eastern border and created a humanitarian crisis of such staggering magnitude that the UN had to intervene. Tens of thousands of Hutu families crossed the border to seek refuge in Congo. The volatile situation led to the First Congo War (1996-1997) that ravaged Eastern Congo as Laurent-Désiré Kabila and his motley crew of rebels and ragtag child soldiers (known as kadogos) fought to oust President Mobutu, Congo’s strongman, from power. It was during that war that Leolina and her family became refugees themselves. After her father was abducted by militiamen, never to be seen again, and Maison Rouge bombed, Leolina and her family fled Uvira and made their way to Zambia, then Tanzania. They ended up at a UNHCR Protection Center in Tanzania after a harrowing odyssey across Lake Tanganyika. The entire family, bereft of her father, whom she describes as having “a heart of gold,” a “good man” who “lived only for other people” (65) and one sister who was shot by rebels, resettled in Québec, Canada.

Juma’s heart-wrenching story of betrayal, war, and displacement is tantalizing and will no doubt captivate her target audience. Unraveling for her readers the often-convoluted ethnic unrest and vortex of war that have wreaked havoc in the Great Lakes Region, she succeeds in conveying the ways in which war tears apart the social fabric of vulnerable communities, displaces civilians, and indiscriminately destroys ordinary people’s lives. Yet, at times, she misses the opportunity to compellingly challenge and dispel the myth of senseless Africa’s unending ethnic conflicts that often percolates in the 24-hour news cycle in the US media. The war in Congo, which some scholars have dubbed Africa’s First International War, pitted powerful international forces and private interests against one another. We get a glimpse of this maelstrom in the book when Leolina and her group of refugees is joined by a weary Frenchman who was also trying to escape Uvira. “Ah, France,” bemoans the man, “it’s all your fault” (83). Rather than seize that opportunity to explain the international stakes of the war in Congo, the author glosses over the lament and leaves the reader wondering why France should be blamed for a conflict unfolding in the heart of Africa.

Reviewed by Didier Gondola, Ph.D., Indiana University-Purdue University, Indianapolis

Published in Africa Access Review (September 28, 2020)

Copyright 2020 Africa Access

Maison Rouge is a memoir narrating the experiences of Leila Liliane Juma during the wars in the Democratic Republic of Congo (formerly known as Zaire) and neighboring countries, namely Burundi and Rwanda. The book was named after the house in which the author spent her childhood in the city of Uvira in Eastern Congo, on the northern shore of Lake Tanganyika. Her father, a highly-regarded man, known for his generosity and praised by all as the “pillar of our community” (67), used their home as a shelter for the disenfranchised, including refugees from neighboring countries. Soon, Leolina (the author and main character) becomes aware of the pangs of war as her home is transformed into an asylum place for the many refugees pouring in from Burundi and Rwanda.

The story starts with the moment she and her family arrived at the refugee camp in Tanzania. In the second chapter, the author reminisces about her life back in peaceful and plush Maison Rouge, then gradually progresses to the wartime and its horrors, followed by the moment they arrived at the UNHCR refugee camp in Tanzania after escaping Uvira on foot and by boat.

The same narration structure is used by Sandra Uwiringiyimana (who also grew up in Uvira) in her book entitled How dare the sun rise: Memoirs of a War Child, a book also recounting the life she endured in war-torn Democratic Republic of Congo. In Uwiringiyimana’s book, the narrative begins with her refugee camp being under attack by militiamen. This allows the reader to delve into the story from the get-go and to remain engrossed by the narrative as events unfolded.

Besides war, Juma’s story addresses other powerful themes such as altruism, compassion, and forgiveness. Leolina teaches great life lessons when sharing her room with a family of refugees, taking care of the wounded, and especially forgiving a rebel soldier who almost raped her and an older woman, Yayabo, who had betrayed her father, thus contributing to his certain demise. This last character trait of hers shows her maturity and psychological strength given her young age (she turns 16 when her family managed to escape from Uvira). Most importantly, it reveals that she is already in a healing process while still going through hard times. Indeed, by heeding her mother’s plea to forgive Yayabo, she exemplifies courage and resilience: “Yes, Maman. Papa taught me not to keep bitterness in my heart. To do that gives power to those who have wronged you” (122).

Couched in a realistic and neutral tone, Juma’s fast-paced narrative is a riveting account that will appeal to young readers. The short vignettes and vivid descriptions, and Juma’s ability to turn wounds into wisdom and pain into power, will no doubt leave a lasting impact on readers. As a young African myself, I would definitely recommend her book to every young reader as a great opportunity to learn about the devastating impact of war on the lives of thriving communities in Congo and the Great Lakes Region.

Reviewed by Isis Dia (Freshman, Indiana University-Purdue University, Indianapolis)