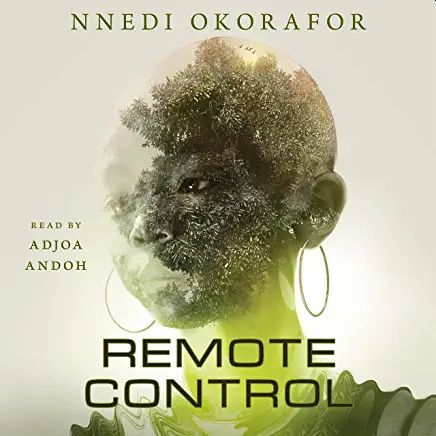

Remote Control

Remote Control

Remote Control

Fiction / YA / Ghana

Tor.com

January 19, 2021

160

An alien artifact turns a young girl into Death's adopted daughter in Remote Control, a thrilling sci-fi tale of community and female empowerment from Nebula and Hugo Award-winner Nnedi Okorafor “She’s the adopted daughter of the Angel of Death. Beware of her. Mind her. Death guards her like one of its own.” The day Fatima forgot her name, Death paid a visit. From hereon in she would be known as Sankofa—a name that meant nothing to anyone but her, the only tie to her family and her past. Her touch is death, and with a glance a town can fall. And she walks—alone, except for her fox companion—searching for the object that came from the sky and gave itself to her when the meteors fell and when she was yet unchanged; searching for answers. But is there a greater purpose for Sankofa, now that Death is her constant companion?

I am often weary when non-Ghanaian writers venture to write about Ghanaian culture. However, Nnedi Okorafor shows that she is a writer worth her salt especially in how she presents Ghanaian life of the near-future. Remote Control is an exciting novella which follows the life of a young girl who is born Fatima, but later changes her name to Sankofa, in the town of Wulugu in Northern Ghana. As early as age 4, Fatima’s love for nature leads her to merge with an element which fell as an aftermath of a meteor shower. This encounter changes the course of her life forever, leading the plot to hinge on her quest to find her life’s purpose whilst navigating life with the strange power that seeks to control her from the inside. As a typical Africanfuturist piece of literature; a genre that Okorafor is famous for, Remote Control presents a fusion of sci-fi, speculative art blended against the backdrop of colourful Ghanaian culture. There are Twi speaking robots that direct traffic and all forms of 3D electronics are rife throughout the land.

Remote Control presents thematic concerns that border on the exploitation of rural communities by political leaders and international corporations, female solidarity, loss and the grief associated with it. In all of Okorafor’s works, the running similarity is the confidence and independence of female characters, especially the protagonists. In Sankofa’s case, her confidence is heightened by the power she possesses. She speaks with confidence, making demands for her satisfaction and in the same breath faces challenges head-on, murdering anyone who dares to cross her path. Aside her confidence, Remote Control also does a good job of highlighting other feminist concerns such as a woman’s right to own a leading electronic distribution store as well as female solidarity. This makes Remote Control an ideal book for contextual feminist studies.

I admire Okorafor’s effort in historicizing the covid-19 pandemic in fiction: “There was talk of a new virus and fear of this resulting in a pandemic faster and more lethal than the one in 2020.” This simple line does a good job of memorializing what has plagued the world for the past 2 years running. Not only is it exciting to see covid being referenced in the past but I believe that it will serve future generations who would have no knowledge of this pandemic and perhaps lead to historical research into it.

Where Okorafor falls short is her inability to fully explore the implication of the name Sankofa. The name change from Fatima to Sankofa comes too abruptly. Moreover, due to the philosophy behind the name Sankofa, which champions the need to return to the past to reclaim that which is at risk of being forgotten in order to build a viable future, the change of name should bear some importance to the plot. Nonetheless, it is possible that on a broader scale, what Okorafor could be subliminally communicating with the name Sankofa is the need to return to nature; the trees, the forests, the insects and the rivers. Okorafor is deliberate in presenting a culture that is moving forward at its own pace whilst maintaining significant cultural elements such as language, clothing and community.

Reading with a Ghanaian lens, it is quite difficult to not be extremely judgemental of some of the cultural elements presented or misrepresented for that matter. For instance, the spelling of the Ghanaian slang “chale” which refers to friend was spelled “chalé” with an accent on the e, however, Ghanaians do not have the accent on the e. Also, there are instances where Nigerian pidgin English “Na artificially intelligent” is used in lieu of Ghanaian pidgin English “E be artificial intelligent”. Nonetheless, Okorafor does a wonderful job of representing the Mamprusi culture as best as she can, especially considering her Nigerian background.

It is possible that the story of Sankofa is just beginning with Remote Control being its first installment. There is much more of the plot to be explored – returning the seed back to its roots could only be the beginning of a deeper and even more thrilling journey for Sankofa and the power she holds. And even more so, one that will truly portray the significance of the Sankofa name in all its entirety. If developed further, Remote Control has the potential of becoming a modern day Ghanaian sci-fi legend that generations will come to cherish for years unend. All things considered, Remote Control deserves 4 strong stars. It is an easy straight-forward one-session read.

Elizabeth Abena Osei, MA

University of Ghana

Published in Africa Access Review (December 22, 2021)

Copyright 2021 Africa Access