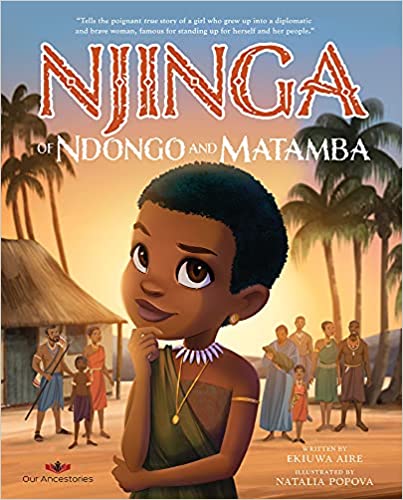

Njinga of Ndongo and Matamba (Our Ancestories)

Njinga of Ndongo and Matamba

Njinga of Ndongo and Matamba

Picture / Biography / Ages 7 and up

August 12, 2020

"Idia of the Benin Kingdom introduces young readers to the story of Queen Idia of the ancient Kingdom of Benin, who played an essential role during the reign of her son, Esigie, who ruled Benin from 1504-1550. This story tells of a young Idia who pursued her dreams, believed in herself, and became the first Queen Mother of Benin. The story starts with a dream young Idia has where she sees a woman in battle. The woman in her dream also appears to be using herbs and potions to heal the wounded. Something about the dream convinces Idia that she is destined to do more for her beloved kingdom. She does whatever it takes to become what her dream had shown her. It wasn't easy because, at the time, young girls were not groomed to be warriors. But Idia was determined to challenge the status quo. Idia is an excellent role model.... After the death of Idia's husband, the Oba, the kingdom was divided. Idia's political counsel helped her son end a civil war. He, in turn, bestowed upon her the title "Iyoba" meaning Queen Mother.

Author Ekiuwa Aire was born in Nigeria where she lived until the age of nine when her family moved to England. She currently lives and writes in Canada. Njinga of Ndongo and Matamba is her second book and the second in a series of non-fiction children’s books published by Our Ancestries about women leaders in African history. Her first book, Idia of the Benin Kingdom won multiple awards including Best Book for Young Children from the Children’s Africana Book Awards (2020). Njinga is attractively illustrated by Natalia Popova in a style that will appeal to young readers.

The picture book begins with Njinga’s dramatic emergence from the womb with her mother’s umbilical cord twisted around her neck. She survived the ordeal with the intervention of her father, Kiluanji. This heartwarming episode of Kiluanji literally breathing life into Njinga establishes the crucial positive relationship in the story. The book follows Njinga’s childhood focusing on her intelligence as shown by her aptitude for schooling and especially her ability to learn to speak Portuguese from her missionary teacher. It continues through Njinga’s mid-life as she struggled to survive and ultimately rose to be queen of her home Ndongo (in modern day Angola) and a neighboring kingdom called Matamba. The book ends with two sections called Just the Facts to provide more context about local kingdoms and Njinga’s life, as well as a useful map. The book includes Kimbundu words on most pages, which lends authenticity and authority to the story.

This is the story of the Ndongo elite during the era of land grabs by Portuguese colonial armies. Kiluanji was a chief (soba) at the time of Njinga’s birth and was soon elevated to ruler (ngola) of the Kimbundu people. Njinga’s brother Mbandi is the main antagonist of her childhood. The presumed heir is jealous of how their father dotes on Njinga. Kiluanji dies after battle when Njinga is a young adult, and Mbandi succeeds him as ngola. Njinga has to flee her empowered brother but is brought back by Mbandi when he begins losing battles and land to the invading Portuguese. He sends her as an emissary to negotiate in colonial Angola. Njinga gains a short-lived peace and Mbandi dies in mysterious circumstances as the Portuguese continue winning land. The book ends with Njinga succeeding Mbandi as ngola, defending Ndongo well (though it is ultimately conquered), and uniting Ndongo with Matamba.

Ekiuwa Aire narrates Njinga with clear, relatable language that highlights some of the most well-known events of Njinga’s life as an example of an African woman who rose to power. Njinga’s rise in a patriarchal warrior society is rare and she should be remembered for her courage, strength, and political cunning. Her story includes several dramatic successes including surviving the twisted umbilical cord at birth (an event that provided her with her name). In another well-known instance she negotiated a peace deal with the Portuguese governor of colonial Angola. She met him in a room where there was only one chair, which he sat in. He offered her the floor to sit on but Njinga had one of her slaves kneel and sat on his back so she could look the governor eye to eye and speak to him as an equal.

Parents and teachers will appreciate a children’s book that tells the story of a strong and intelligent African heroine but there are serious concerns. One of Njinga’s greatest gifts was building alliances at just the right time to accomplish her ambitions. She twice entered into friendship with the Portuguese by adopting Catholic baptism to end their violence against her. These are not mentioned in the book at all. Two other military alliances referenced in the Just the Facts sections, those with the Dutch and the Imbangala, were key to her rule in Ndongo and Matamba. Demonstrating Njinga’s cunning and political astuteness as an alliance builder in the story would highlight one of her strengths and help clarify how she was able to hold off the Portuguese for so long when Kiluanji and Mbandi could not.

The most serious concern, and the one that adults will need to frame for children, regards slavery. The text and illustrations are clear and accurate when referencing the Portuguese as slavers. However, the text ignores Njinga’s involvement with the inhuman trade. As a warrior queen she successfully kept the Portuguese at bay and maintained political power, which the book portrays well, but she also generated thousands of war captives who were enslaved and sold to the Dutch. Other recent portrayals of Njinga similarly ignore how Njinga benefited from warfare and slavery so there is precedence to tell this story without referencing her as a slaver in the narrative. Still, a mention of it belongs in the Just the Facts section.

Further, the book errs by referring to the people who staffed Njinga’s personal retinue, called mukua-mbele in Kimbundu, as “helpers” instead of slaves. This translation occurs twice in the book. For example, the person who Njinga sits on while negotiating with the governor is called a helper. These folks in Njinga’s service were unfree and expendable; they were enslaved and the story should be honest about that. Slavery arrangements in African communities can be difficult to understand, especially for those who are only familiar with the chattel slavery of plantations in the Americas. I sympathize with the author who cannot complicate a children’s book with analyses of unfree labor systems. But, using euphemisms to talk about slavery risks robbing those who were enslaved of their humanity once again. The author should ignore these stories if they don’t want to link Njinga to slavery. Or preferably, the author could revise the translations so children see Njinga as a fully human heroine – flawed but also talented, intelligent, powerful and successful.

Reviewed by Jared Staller, Ph. D., St. Francis Episcopal School

Published in Africa Access Review (July 2, 2021)

Copyright 2021 Africa Access