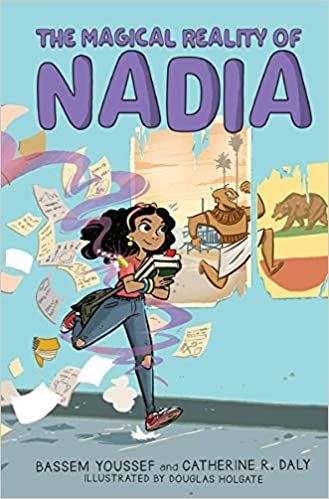

The Magical Reality of Nadia (Magical Reality of Nadia, Book 1)

The Magical Reality of Nadia

The Magical Reality of Nadia

Fiction / Elementary / Middle School

Scholastic Incorporated

2021-02

176

"Inspired by the author's . . . experiences, this . . . novel follows sixth grade Egyptian immigrant Nadia as she navigates the ups and downs of friendships, racism, and some magic, too! Nadia loves fun facts. Here are a few about her: she collects bobbleheads--she has 77 so far ; she moved from Egypt to America when she was six years old ; the hippo amulet she wears is ancient--as in it's literally from ancient Egypt ; and she's going to win the contest to design a new exhibit at the local museum. Because how cool would that be?! (Okay, so that last one isn't a fact just yet, but Nadia has plans to make it one.) But then a new kid shows up and teases Nadia about her Egyptian heritage. It's totally unexpected, and totally throws her off her game. And something else happens that Nadia can't explain: Her amulet starts glowing! She soon discovers that the hippo is holding a hilarious--and helpful--secret. Can she use it to confront the new kid and win the contest?" Follett

Searching for a book to recommend to my 10-year old Arab-Mauritian-American daughter, whose identities are grounded across cultures and countries, I turned to The Magical Reality of Nadia, wondering how it addressed the theme of interculturality and belonging. The book is centered on the story of Nadia, a studious 6th grader whose parents emigrated from Egypt to the United States when she was a young child. Nadia prides herself in knowing “fun facts” – trivia about ancient Egypt – which are dotted throughout the book. Her four friends are each from different cultural backgrounds, coming together in a group who call themselves “the Nerd Patrol.” The plot is articulated around a magical happening: an ancient Egyptian teacher named “Titi” appears in the form of a cartoon when prompted by an amulet that Nadia brought back from her recent vacation to Egypt. The group of friends develop a school project for the local museum of American history on “What makes America, America” (p. 26). They choose to tell the stories of their families’ arrival and immigration to the United States. In school, Nadia experiences racism from a classmate who makes fun of aspects of Egyptian culture and identity and negatively compares them against his white anglo-American norms. Titi uses his magic to help the Nerd Patrol complete their project – a performance of all the ways immigrants to the United States have built this country.

The strengths of this book lie in the ways the author inserts aspects of Egyptian culture into Nadia’s identity and in the story overall. Teachers who wish to discuss the complexities of diasporic, multicultural identities will find this material useful and generative, particularly because the narrative represents Nadia as negotiating multiple identities, and as a young person with agency over her self-representation. She is proud of her heritage; she asserts herself as she rejects racist remarks from her classmate, and grapples with learning multiple perspectives from her group of multicultural friends. Egyptian American students will find little bits of “home” in the specific references to beloved foods like Kushary or the way she calls her father “Baba.” The influence of ancient Egyptian history is also noteworthy. Students will learn the origins of toothpaste, mathematics, and papyrus to expand their knowledge of modern contributions of ancient Egyptian civilizations. While not central to the plot, the parents’ story of fleeing Egypt after protesting to topple the Mubarak regime offer an important historical glimpse into the revolts of the Arab Spring and the ways this shaped the experience of a family.

However, there are several major problems with this book: one is the way modern Egyptian culture is directly and uncritically linked to ancient Egyptian history, with references embedded throughout the book. This erroneous linkage is not surprising, given the extent to which the current Egyptian state invests into tracing a linear connection between ancient Egypt as a precursor to the modern nation-state, a discourse that builds a grandiose millennial narrative of the grandeur of Egypt, often with the function to hide its present failures.

Second, the immigration project – “Immigreat” – that the students develop to present at their school is underpinned by antiquated melting pot ideologies that feed into problematic notions of the United States as an opportunity for advancement for all. One friend of Nadia’s explains: “our country’s story is not just that of scientists and authors and inventors (…) it is also the story of ordinary people who came here to make this nation their new home” (p.141). More egregiously, the narrative of immigration and belonging actually erases the experiences of Native Americans and Black Americans and glosses over centuries of enslavement and genocide. Native Americans are briefly mentioned two times, and there is one mention of enslavement. The story favors the theme of immigration in a way that whitewashes its history. Nadia describes: “unless you are Native American, we all have an immigrant story in our past. Each of us is here today because one of our ancestors came to America and started a life for their family” (p. 152, emphasis added by author). A vague mention of a “difficult history” follows when Sarah, who is her friend from Jamaica, says “our ancestors went through a lot to get us here (…) there are some things -hard things- we wish they hadn’t had to go through” (p.148). However, this snippet is so elusive that it does not justice to the histories of enslavement, indenture, and genocide that were formative to the founding of the United States.

Author Bassem Youssef is a renowned Egyptian surgeon, comedian, and political activist who left Egypt after the military took over. He has had a public presence on CNN and other media, and is well-known in the Arab world. He has succeeded in writing a novel that captures the complexity of diasporic identities and is developmentally written for upper elementary and middle school readers. However, the imperative to squarely face the racist founding of the United States and the way it still differentially impacts social groups makes the narrative around immigration partial, erroneous, and ultimately educationally unacceptable. My daughter enjoyed reading about many aspects of Nadia’s life. However, we had very critical conversations about the history it presented, which is how I suggest all teachers and readers should approach this book.

Elsa Wiehe, Ed. D. Boston University

Published in Africa Access Review (June 9, 2021)

Copyright 2021 Africa Access