Small Mercies

Small Mercies

Small Mercies

Fiction / Elementary / Middle / Ages 8-12

Catalyst Press

February 4, 2020

162

"Mercy lives in modern-day Pietermaritzburg, South Africa with her eccentric foster aunts--two elderly sisters so poor, they can only afford one lightbulb. A nasty housing developer is eying their house. And that same house suddenly starts falling apart--just as Aunt Flora starts falling apart. She's forgetting words, names, and even how to behave in public. Mercy tries to keep her head down at school so nobody notices her. But when a classmate frames her for stealing the school's raffle money, Mercy's teachers decide to take a closer look at her home life.

Along comes Mr. Singh, who rents the back cottage of the house on Hodson Road. When he takes Mercy to visit a statue in the middle of the city, she learns that the shy, nervous "Mohandas" he tells stories about is actually Gandhi, who spent a cold and lonely night in the waiting room of the Pietermaritzburg train station over a hundred years ago. It marked the beginning of his life's quest for truth...and the visit to his statue marks Mercy's realization that she needs--just like Gandhi--to stand up for herself.

Mercy needs a miracle. But to summon that miracle, she has to find her voice and tell the truth--and that truth is neither pure nor simple. " Publisher

Mercy Adams, an eleven-year-old, lives with her two foster aunts in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. Her mother was killed in a car accident when Mercy was just four years old, and she doesn’t know who her father was. The elderly aunts, sisters Mary and Flora, have a difficult time making ends meet, but their love and kindness toward Mercy are generous. At school, where Mercy is in grade six, she is shy and self-conscious, often reluctant to participate in class assignments such as performing a folk dance from her culture, but at the same time bright and perceptive. When things at home seem to be falling apart—a developer wants to take over their property and Aunt Flora’s dementia worsens—Mercy worries that her social worker will take her away from the home she loves. However, when the aunts decide to rent their backyard garden cottage to Mr. Singh, the situation seems to improve, until Mercy is accused of stealing the school’s raffle proceeds. The resolution allows Mercy to find her agency and bring a satisfying ending.

Bridget Krone’s debut novel shines as an example of life in the new South Africa. While realistic about the effects of poverty, caregivers’ struggle to provide effective care, and child abuse, the narrative is not message-heavy. These themes are subtly integrated with others about an endearing child who needs love and security, who closely observes what is happening around her and sometimes finds it confusing or worrisome, and who ultimately finds her voice. Mercy receives important help from adults in her life, but she and her classmates cleverly play the starring roles against the malevolent developer Mr. Craven. A reader will root for her all the way, until she lives up to her name, which Mr. Singh explains signifies a blessing for both the giver and receiver. In the end, Mrs. Pruitt, her teacher, appraises her with new regard, “Mercy Adams, I think there’s more to you than meets the eye” (p. 187).

Mercy’s character is fully developed and grows as she becomes more confident in her capabilities. The aunts, Mr. Singh, and Mrs. Pruitt all play supportive roles with empathy and relate to her non-judgmentally. Her classmates behave like typical kids, who like to tease and misbehave but are good-hearted in the end. The most stereotypical characters serve their roles—Mr. Craven as the villain who gets what he deserves and the flamboyant Doctor Waku from Senegal as the dispenser of happiness and solver of problems. Several kindly neighbors fill in the cast of characters, and the famous Mohandas Ghandi serves an important supporting role in Mercy’s development.

Especially commendable is the author’s ability to embed information about South Africa’s historical and contemporary context, including Mr. Ghandi’s importance in the struggle against apartheid, Mercy’s ethnicity as “Coloured,” the cultural mix of Mercy’s schoolmates, Mr. Singh’s Indian influence, and the aunts’ European roots. Contrasted with the matter-of-fact manner in which these aspects are all handled, the stereotype of Doctor Waku (reminiscent of “wacko”?), as the Senegalese immigrant, seems a bit gratuitously comical.

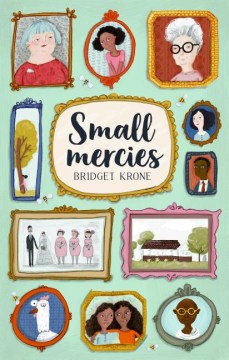

That misstep aside, this novel brims with poignancy, worthwhile themes, memorable characters, lively dialogue, humor, language-play, and sensitivity. Krone’s background as a creator of materials for South African school text books undoubtedly honed her graceful, engaging writing skills and emphasis on the primacy of a good story to convey her message. Cape Town resident Karen Vermeulen’s spritely cover and chapter-heading decorations nicely complement the text. “Small Mercies” is the perfect title for this delightful read.

Barbara A. Lehman, Professor Emeritus, The Ohio State University

Published in Africa Access Review (August 1, 2020)

Copyright 2020 Africa Access