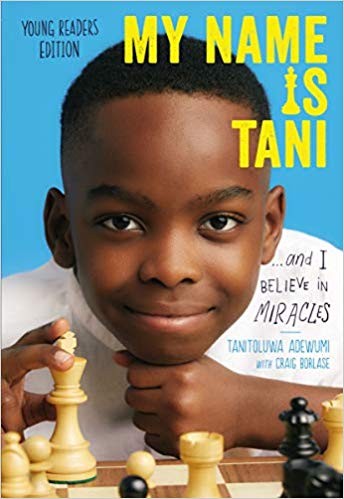

My Name Is Tani … and I Believe in Miracles Young Readers Edition

My Name Is Tani ... and I Believe in Miracles Young Readers Edition

My Name Is Tani ... and I Believe in Miracles Young Readers Edition

Upper Elementary / Ages 9-12 / Biography

Thomas Nelson

April 14, 2020

200

"At eight years old, Tani Adewumi, a Nigerian refugee, won the 2019 New York State Chess Championship after playing the game for only a year--and while homeless. His story is full of miracles and hope.

This adaptation of an adult book focuses on the portions of Tani's story that will most interest young readers. The struggle of leaving his comfortable home and moving to a new country with nothing. Living in America as a homeless family. Having no TV, no games, no money. Wanting a place for his mom to cook meals and a refrigerator where he could get a snack whenever he was hungry. Going to a new school. Meeting a teacher who taught him the game of chess, which allowed him to learn, compete, and experience the pressures of the game and the ultimate joy of winning." Publisher

This upper elementary chapter book is the story of a Nigerian refugee family who left Nigeria because of harassment by terrorists of the Boko Haram group and their early experiences in New York City. The younger son, Tani, became a chess champion at the age of 8 and is the focus of this story. We read of the family experience from their arrival in New York, getting settled and the two children experiencing their first days in school. The bulk of the book focuses on Tani’s growing interest in and love of chess.

The best parts of the book are the excitement and challenge of the tournaments. As with the recent Netflix series, “The Queen’s Gambit,” one does not need to know how to play chess to find these chapters compelling. Some of the sidebars include brief descriptions of how to play chess, and Tani’s chess tips are interspersed throughout the book.

Large gaps and omissions in the broader context of refugee experience, however, and errors and omissions in informational sidebars are concerning. Details of how and when the family is able to leave Nigeria are omitted. This refugee experience is misleading and simplistic. Soon after the second encounter with Boko Haram, the family is on a plane to the US, arriving for a stay with family in Dallas. Shortly, they are on a bus to New York City, filling out paperwork and placed in a shelter. There is no acknowledgement of the visa process, a wait, or delay. Every transition and opportunity is because of a miracle and divine intervention: “God rescued us.” (10) As the terrorists banged on the door, the Dad watched and prayed and made noise. “So they [Boko Haram] ran away. Another miracle.” (15)

Given the intricacies of refugee restrictions, which were tightened beginning in 2017, understanding the backstory of sponsorship is key to grasping how Tani’s family navigated their journey. The article leaves readers questioning how they managed to secure a visa so promptly. We’re not privy to the details of their departure from Nigeria or their initial steps in New York City, where the narrative shifts to more familiar ground: the parents working in typical low-wage jobs, as an Uber driver, and a nursing assistant. Yet, as Tani’s chess victories propel them into the spotlight, their circumstances improve significantly. They receive donations, a car, and an apartment—a place where “my home value” takes on new meaning, not just in monetary terms, but as a foundation for a brighter future. The funds also enable the family to give back, establishing a foundation to support other children and families in similar situations.

The text and sidebars include sanitized and inaccurate historical information. The reader is told that Boko Haram are really bad people because they “decided that they wanted to kill Christians.” (10). In truth, Boko Haram terrorists have killed and kidnapped Muslim and Christian alike, especially those attending Nigerian government schools. The rosy description of immigrants in the U.S. sugarcoats history and neglects to mention any historical or recent anti-immigrant attitudes. (4) A description of Rosa Parks omits her role as a civil rights activist and more than a tired bus rider (84-5), information that is now widely available. In recalling a school lesson, Tani describes learning about Martin Luther King, Jr, Malcolm X and Nelson Mandela. He notes that the sad part was learning that King was shot and died and became a martyr. No mention is made of Malcolm X’s assassination (180). As with so many stories of African immigrants, the authors state that Tani’s father is a Nigerian prince.

This is a Christian publisher and there is much proselytizing. “God is with us.” (6-7) “God is good to us.” (110) After each chess match, Tani’s parents ask, “Did you say thank you to God?” (173) The opportunities the family experienced are rarely described or explained. They are miracles and God is responsible. Not recommended.

A companion picture book, Tani’s New Home, A Refugee Finds Hope and Kindness in America, has also been published. This is a much-shortened version of Tani’s story. His quiet, secure Nigerian home is disrupted by Boko Haram, who “…hurt people who disagree with them.” (4) This statement is more accurate than the descriptions in the chapter book. The story jumps to New York City and Tani’s learning chess in school, becoming a champion and receiving a car and home after fundraising and publicity. An afterward notes, “Tani has learned that with God ‘anything is possible.’” The illustrations are warm and expressive. Advisory recommendation, two stars

Reviewed by Jo Sullivan, Ph.D. Independent Scholar

Published in Africa Access Review (January 29, 2021)

Copyright 2021 Africa Access