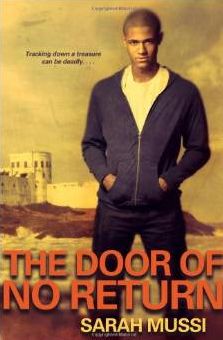

The Door of No Return.

The Door of No Return.

The Door of No Return.

Historical Fiction, MIddle, High,

Margaret K. McElderry

2008

,ISBN 9781416915508

Sixteen-year-old Zac never believed his grandfather's tales about their enslaved ancestors being descended from an African king, but when his grandfather is murdered and the villains come after Zac, he sets out for Ghana to find King Baktu's long-lost treasure before the murderers do.

The Door of No Return is a novel aimed at young adults. It is structured vaguely as a diary of the events that surround its protagonist, Zac Baxter, paralleled by excerpts of the slave narrative of his ancestor Bartholomew Baktu some three hundred years before. The plot of the novel sends Zac from the UK in search of his ancestor’s buried treasure and his own heritage in coastal Ghana. Neither of these characters in entirely believable – Bartholomew’s narrative is entirely unlike any of the accounts left by enslaved Africans and Zac’s attempts at Gloucestershire street lingo seem a bit forced. Nevertheless, the literary device of paralleling the stories of the two is effectively played out and the modern-day Baxter an enjoyable hero and one designed to capture the attention of cell phone-toting young readers.

As a thriller, the novel is at times engrossing and at times a bit silly. In this day-and-age of Iraq war era inefficiency it seems laughable to portray the British intelligence agencies as conspirators, and at times it seems that they are being stretched in an attempt to parallel the evil-doing of the eighteenth century British slave-trading administrators of Cape Coast. Quite clearly, the British are the bad guys of this story, although the author takes care to throw in some just white folks as friends and protectors and to raise the question of black or African collaborators both in the slave trade and in the modern conspiracy to chase Zac down.

The treasure of this story is not just gold, although there’s an awful lot of it in a chest hidden by Bartholomew Baktu and his brothers in Cape Coast Castle just before their enslavement and waiting for Zac to come and claim it. Instead, the story touches on two deeper treasures. The one is Zac’s heritage as a lost prince of Africa, which he regains upon returning home to an island in the Pra River. The other is justice, in the form of a bond allegedly written by British officials promising not to enslave the Baktu and which, if it can be brought to light by Zac, can win millions of pounds in reparations for their descendants in Africa, the Caribbean, and the UK.

The story unfolds very much as a heritage story with a political undertone of support for reparations. Like many others of this sort of tale, it harnesses history to do so. The plot was inspired by a dispatch in Dutch colonial archives of a hidden treasure at Fort St. Sebastian in Shama. However, the author relocates the story to Cape Coast partly because it is more dramatic and partly out of respect for the fact that the castle is now a world heritage site (393). The title of the book is reinforced by numerous references to the doors of no return allegedly used to dispirit slaves leaving Africa for the last time, although the authenticity of these doors has at times been questioned. History is mobilized with authority throughout the book, and the author argues that she has taken all of her facts from a true source (393). These sources comprise the curators of local forts, oral historians, and several popular histories including Albert van Dantzig’s excellent work on forts of the Ghanaian coast. Setting aside the problems with many of these sources in terms of accuracy, it is unfortunate that the author sought to portray her work partly as a History when it is really a work of heritage that has admittedly been reworked to suit her objectives. The fact is that the novel liberally cuts and pastes historical event in pursuit of contemporary goals. As a novel it has the capacity to interest young people in modern transnational identities like Zac’s and in Africa as a complex, multifaceted and interesting place. The author should be congratulated on her ability to help readers question their assumptions in this regard. In dealing with the past, it descends sometimes into crude characterizations of good and evil and anachronistic depictions that are appropriate in a literary genre such as this one but not necessarily in depicting historical processes. This is not to say that the book isn’t a worthy read. I will be passing it on to my children, certainly. But it does leave me wishing for a more thoughtful consideration of the meanings of the slave trade that relies less on flashy and well-worn symbols like doorways of no return and lost princes of Africa and more on complex and rich depictions of past peoples and events.

Copyright Africa Access 2009

Reviewed by: Trevor Getz