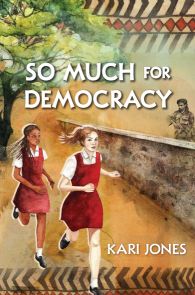

So Much for Democracy

So Much for Democracy

So Much for Democracy

Historical Fiction / Elementary / Middle

Orca Book

2014

ISBN-13: 978-1-45980-481-4

The political upheaval in Ghana in 1979 puts Astrid and the rest of her Canadian family at risk.

As I took in the title of the book and read the back cover with an illustration of a soldier holding what looks like an AK 47, I began to have a sinking feeling in my stomach. In bold red were the words snakes, spiders, soldiers and sand! Coupled with the words “family adventure” and “disaster,” how could this book be good? It isn’t, at least not with regard to the depiction of Ghana. Jones is a good writer. She crafts believable characters, good dialogue and a well-paced plot but her ability to feel, know and reflect Ghana is lacking. She writes from an outsider perspective that to this Ghanaian is not familiar.

The setting for the novel is Ghana during a period of political instability in the late 1970s. The country’s instability mirrors the fragility of a Canadian family as they cope with the stress of living in a foreign country. A Canadian civil servant accompanied by his wife and three kids has come to Ghana to help with the impending election perhaps supported by the Canadian government and intended to bring some good to the political fortunes of Ghana. They arrive at a politically perilous time when the Ghanaian military headed by Jerry Rawlings has become extremely involved with politics through coups d’état.

The story’s narrator is Astrid, the oldest child. She is a strong-willed young girl who is open-minded enough to accept the obvious changes her overseas trip brings. She attends a Ghanaian school, quickly makes friends, especially with Thelma Ampofo a good-natured Ghanaian girl. Astrid is also close to Thomas, the gardener, who is saving money to buy a house with his wife Esi, a market woman. Astrid’s adjustment to Ghana is destabilized by her paranoid, overprotective mother who does not want to be in a place as “unsettling” as Accra. In Canada Astrid tells us, Mom is normal but in Ghana, she “thinks there’s danger lurking everywhere … [she] is in way over her head, and she figures the sooner Dad’s done his work with the election the sooner she’ll be able to get us all out of here” (4). Soon Astrid is listing all the ways (thirty-five) she hates Ghana, “….power goes out….soldiers….spiders, snakes, and mosquitoes…nasty-tasting malaria pills…having to boil water….When I finally run out of things I hate about Ghana, I lie down and fall asleep” (23).

Gordo, Astrid’s younger brother makes the most successful adjustment. He enjoys adventures with neighborhood boys and even learns to speak Twi, a local language. Astrid realizes how little she has learned about Gordo’s playmates towards the end of the book when she sees how concerned he is about the boys when political trouble erupts, “To him they are more than just boys who live in the neighborhood and sneak up the drive to hang out at our house. They are his friends….I’ve never even learned which boy is Kwame and which is Yafeo” (146).

After a couple of meltdowns, Astrid’s mother also makes an adjustment but just a slight one. She decides to stay for their tour of duty instead of taking the children back to Canada but she cautions Astrid, “… it is dangerous here…Things are still unsettled here. We need to look out for each other” (168). Interestingly while Astrid’s family stays in Accra, Thomas the gardener, a Rawlings’ supporter, leaves for Kumasi. Disillusioned with Rawlings and fearful of the violence, he tells Astrid, “We have to go–you know we do. Esi’s afraid to go back to the market. There’s nothing for her to do here. There’s no future for us” (159).

Ultimately this a story about a Western white family’s adjustment or lack thereof in an African country. Ghana hovers in the background unknowable, unpredictable, and threatening. One wonders why the author picked this troubled period—almost 40 years ago—to center her story. Ghana has experienced over two decades of peaceful transitions to power. It’s a pity readers will not learn about democratic Ghana in So Much for Democracy. In her ‘Historical Note’ Jones writes, “Today Ghana has a democratically elected leader.” This tidbit about democracy in Ghana is too little and far too late.

Reviewed by Akwasi Osei Ph.D., Delaware State University

Published in Africa Access Review (April 2, 2015)

Copyright 2015 Africa Access