All Rise: Resistance, Rebellion and Revolt in South Africa

All Rise: Resistance, Rebellion and Revolt in South Africa

All Rise: Resistance, Rebellion and Revolt in South Africa

Graphic Novel / South Africa / YA

Catalyst Press

April 5, 2022

220

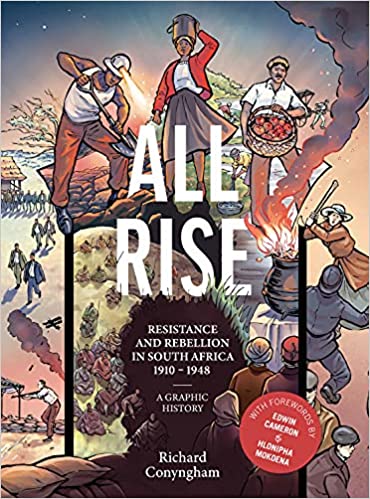

All Rise: Resistance and Rebellion in South Africa revives six true stories of resistance by marginalized South Africans against the country's colonial government in the years leading up to Apartheid. In six parts--each of which is illustrated by a different South African artist--All Rise shares the long-forgotten struggles of ordinary, working-class women and men who defended the disempowered during a tumultuous period in South African history. From immigrants and miners to tram workers and washerwomen, the everyday people in these stories bore the brunt of oppression and in some cases risked their lives to bring about positive change for future generations. This graphic anthology breathes new life into a history dominated by icons, and promises to inspire all readers to become everyday activists and allies. The diverse creative team behind All Rise, from an array of races, genders, and backgrounds, is a testament to the multicultural South Africa dreamed of by the heroes in these stories--true stories of grit, compassion, and hope, now being told for the first time in print.

Author Richard Conyngham is a South African-born writer now living in Mexico City. To call him the author of All Rise seems a bit reductive. He writes the text; and he also did the archival research necessary for it, amassed and led a talented team of artists, and shepherded what is in many ways a collected volume of stories into a well-crafted and highly focused exploration of life in pre-Apartheid South Africa. All Rise contains six stories each brought to life by different artists: Saaid Rahbeeni, The Trantraal Brothers (André and Nathan), Liz Clarke, Dada Khanyisa, Tumi Mamabolo, and Mark Modimola. The artists are award-winners whose unique styles bring a reality to these stories that likely wouldn’t exist with words alone.

The novel is set in the South Africa in the decades prior to the institutional racism of Apartheid. The six stories are not connected by any characters. The reader is tasked, productively, with making narrative connections between the stories that span different decades, places, and communities in South Africa. The stories trace the lived histories of everyday folks who challenged the increasingly restrictive laws of South Africa. We follow Indian business owners who want to bring their families to live with them, mine workers agitating for better working conditions and wages, and women who want to maintain their right to travel freely without showing papers to government officials. Since Conyngham relied on legal archives – court cases – to tell these stories, All Rise is an exceptional look into how common people interacted with the courts to shape their communities.

The first story follows the troubles of three Indian immigrants in South Africa caught in increasingly tight immigration laws. The men try to navigate the ability to see their families in India or bring those families to live with them. Mahatma Gandhi plays a role in this story, the only time in the book we see a historical figure with global fame. The next two chapters follow the trials of two Irish immigrants caught up in the international workers movements of the early 20th century, both of whom experienced violence from the state for their unionization activities. The fourth story is about women who intentionally got arrested for violating new laws that required women to carry passes like men. Since women often traveled outside of their communities to work as domestic servants in white peoples’ homes, these laws were particularly burdensome. The fifth chapter is a fascinating examination of the internal politics among the Bakofeng people, as factions within their kingdom vie for direction in the face of encroaching colonial authority. All Rise ends with the story of a Witwatersrand mine worker who traveled to Johannesburg for work and ended up injured in the police actions against striking miners who sought better conditions and pay.

Individually, the stories are engaging because they are the stories of everyday people. The action doesn’t revolve around a huge concept like ending racism but focuses on the activities of people as they sought better wages or protested unfair restrictions against their movements. These people want immediate and tangible relief to specific problems or restrictions in their lives. Taken as a whole, the reader gets a generous view into South African society in the decades before Apartheid. On this point, the illustrations are more important than the words. Capturing various communities with depth and detail, the artists provide a wealth of knowledge about food, street culture, architecture, technology, and clothes. South Africa, from the mines to the cities to the countryside, is brought to life by the artists and that glimpse into the material life of South Africa makes the drama in the stories seem more real.

Another significant contribution to both the drama and the significance of All Rise is the fact that stories about everyday people feel more contingent, more contested, than stories of well-known figures. We know Gandhi ultimately succeeded in his mission (to cite a figure in the book) so sometimes stories about his struggles are harder to empathize with. If we know the end of a story, it can be easy to miss the difficult choices that led to that conclusion. But since we know none of these characters, the drama is more immediate. Conyngham deserves a lot of praise for making this conscious choice. Not all of the people succeed in their struggle. Some lose their court cases. Others only win a portion of what they wanted. And that makes their struggles feel more real too.

Conyngham and the artists deserve a lot of credit for creating a book that is engaging, well-researched, and visually interesting. I kept coming back to the word “generous” as I thought about this book. Checking in at 248 pages, it is long for a graphic history. The author uses that space to provide an excellent sampling of the primary sources used in each story, including written and photographic sources. From these real pictures, the reader sees how the artists (in their own style) brought the drawn characters to life. The book is also generous in treating everyone in South African society with humanity. There are no straw men, villains or saintly heroes. People make choices in their time and place within the options available to them. All these people chose to rise, and their choices are remarkably human.

Parents and teachers alike will appreciate All Rise for bringing to life stories that are both very local to South Africa while at the same time universally important tales of human resistance and strength in the face of injustice. Some may object to the strong language in a couple of the stories although the language makes sense given the struggles people were going through and isn’t in any way inappropriate to the historical narrative. Also, there are difficult topics like murder, police violence against workers, and capital punishment.

Teachers who use the book in the classroom will find it an invaluable resource. Besides the primary sources there are also ample citations that can be used for further reading, a glossary of South African terms, and other useful supplemental materials. For those of us teaching outside of South Africa, students will need a bit more introduction to the various racial groups in South Africa as well as some geographic knowledge. But, good books should encourage students, and all readers, to do more research. All Rise is an outstanding and engaging graphic history bringing to life in wonderful visuals the reality of resistance to encroaching institutional racism in the 20th century.

Reviewed by Jared Staller, Ph. D., St. Francis Episcopal School

Published in Africa Access Review (July 8, 2022)

Copyright 2022 Africa Access