Born on the Water

The 1619 Project: Born on the Water

The 1619 Project: Born on the Water

Nonfiction / Kongo KIngdom / Angola / Ages 5-8

Penguin

2021

48

Stymied by her unfinished family tree assignment for school, a young girl seeks Grandma's counsel and learns about her ancestors, the consequences of slavery, and the history of Black resistance in the United States.

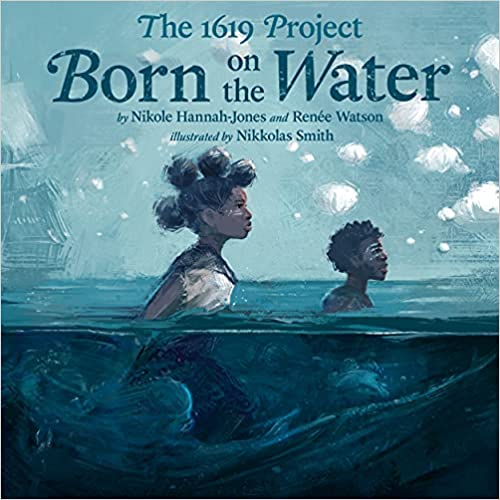

Born on the Water is a spin off product of the New York Times and Nikole Hannah-Jones’ enormously successful 1619 Project, a book aimed at elementary school aged children. Authored by Hannah-Jones and Newbery Award winning co-author Renée Watson, it delivers a story, accompanied by glorious and dramatic illustrations by another award-winning artist, Nikkolas Smith. The story takes on a dilemma which African American children (at least those in majority White schools) might still face today, a class assignment that asks them to trace their ancestry to another country and draw its flag. Realizing that they do not seem to have an ancestry past three generations, and learning that they were “born on the water” and thus without any meaningful ancestry, they turn to their grandmother, who assures them they, too, have a story.

What follows is a traditional “up from slavery story”, but with a new twist: instead an unidentified African country, this one is set in the specific events of 1619, that is the arrival of the famous “twenty and odd Negroes” at Jamestown. The children who read this book or have it read to them then learn some details which are not in the usually generic slavery story: that their ancestors came from a real country, Ndongo, and spoke a specific language, Kimbundu.

What follows, however, is not the story of the actual events in 1619 but a retelling of the traditional narrative of the slave trade, with a few gestures to the real story thrown in. Many factual elements of the origins and fate of the protagonists are not in the 1619 Project, and appear to be mostly unknown to the authors.

The traditional story presented here, whose template might have been something like the 1977 version of “Roots” has a happy, stress-free Africa with agriculture, trade, industry and commerce. This peaceful place is then suddenly disrupted by the White people who manage to seize them and put them on a ship, where they suffer greatly. They arrive in a strange new land where they labor and suffer some more, but eventually manage to secure their freedom and their dignity. It ends as they finally approach becoming normal citizens in an America moving slowly in that direction.

How should historians, who are also parents and who read bedtime stories to their African descended children, look at this book? Parents wishing to ensure that their children have an ancestry story that will make them proud, should have no problems with the story. Historians of the 1619 event, however, would not be as pleased.

The 1619 story, by an interesting set of documentary coincidences, is not the traditional story and we know this because both the African and American end are unusually well-documented. In the African case, seventeenth century West Central Africa is described by literally thousands of pages of first-hand accounts. This plenitude of documentation allows historians to learn about all the elements of culture and are also illustrated by dozens of eyewitness illustrations that show clothing, weapons, tools, plants, houses and in some measure daily life. Even their Kimbundu language is known in its seventeenth century form by a catechism, in Kimbundu, published in 1629, but in use well before 1619 in oral form. The amount of detail of this setting is known in the academy, but not, apparently by anyone associated with the book.

And on the American side, the exact name of the ships on which they traveled, the route they took, and their arrival in Virginia are also well described, and even the subsequent lives of those Mbundus have an unusually long and large paper trail for people arriving from Africa in America.

The documented story is not like the experiences of the vast numbers of Africans enslaved in Africa and carried to the Americas. In the common African experience, it was not White men who did the enslaving, but ironically in the Angola case of 1619, Europeans did indeed lead the attack that enslaved them. Even here, though the bulk and especially the front-line shock troops, Imbangala bands, were too horrible to speak of to children. Imbangala grew their army by enslaving children, and they turning them into ruthless warriors like the child soldiers one encounters in many irregular armies in Africa and Asia today. Most of the rest of the soldiers were subjects of a rival branch of Ndongo’s royal family who, like the Imbangala, allied with the Portuguese.

They did not board the White Lion, as the story says, probably wisely simplifying the complexities of the real first slave ship, the São João Bautista’s transatlantic voyage. That ship, suffering abnormally high mortality had to stop in Jamaica where it left some of the sicker people behind. Back at sea, it was captured by English privateers, sailing in the White Lion and Treasurer, which probably involved a frightful naval battle, especially for those Mbundu captives below decks who could only guess what awaited them.

Once in Virginia, the story gets closer to the reality of seventeenth century America, but perhaps not close enough. There were no whips and chains for these people, they worked side by side with White indentured servants and equally endured the harshness of life on tobacco plantations. And like those Whites, many were granted their freedom after a period of time.

The book then features the life of Anthony Johnson, perhaps known in Ndongo as Antonio João. He was freed quite soon, became a landowner and relatively prosperous, like a number of other of his Mbundu neighbors who suffered the same fate. He might well have been a Christian in Angola and this perhaps contributed to his rise. The “up from slavery” narrative was quite a bit better for them than for those who followed, all the more so since the White Lion freed them from the fate they would have suffered had they reached their intended destination of Vera Cruz, Mexico. Had they reached Vera Cruz as hundreds of their shipmates on the São João Bautista did, they would have been put to work on sugar plantations, the harshest of the labor regimes in the Americas.

One more missing element of the story of course, is that if the children in the story are in today’s world, they might have gone to their parents, who would turn to the genetic profile recently sent them by an ancestry tracing company, and would have said, well, your ancestors came from Senegal, Ghana and Angola, and here are their flags.

Reviewed by John Thornton, Ph.D. and Linda Heywood, Ph.D.

Boston University

Published in Africa Access Review (May 27, 2022)

Copyright 2022 Africa Access