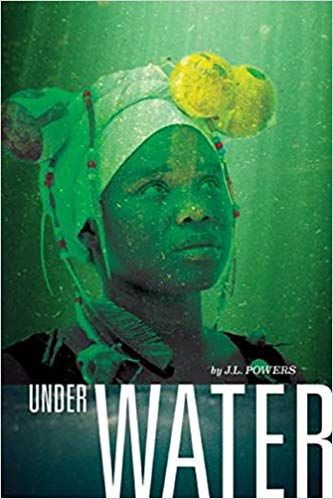

Under Water

Under Water

Under Water

Young Adult / Fiction / South Africa

Cinco Puntos Press

2019

184 pp.

When her beloved grandmother dies, 17-year-old Khosi must learn to survive on her own. She has to take care of her little sister Zi, make a living as a traditional healer, and somehow try, despite everything, to finish school. When her beloved Imbali―an urban township in South Africa―flares up in violence, Khosi finds herself at the center of the storm.

Under Water is a well-crafted narrative written by an American author who is clearly very conversant with Zulu culture, cosmology, and the lived realities of ordinary South Africans in the post-Apartheid era. Were this review oriented to a South African audience it would be very positive and complimentary of the author’s knowledge of and sensitivity towards contemporary manifestations and ambiguities of religious and health belief and practice and the harsh socio-economic realities of urban life in South Africa. Moreover, recognition would be given to the author’s skill as a storyteller, hooking the reader with the growing tension of the narrative while accentuating the strength and resilience of a strong female protagonist. The book, which clearly, sensitively, and in an engaging manner deals with issues that are lived realities of many South Africans, would earn a rating of Highly Recommended.

However, there is no indication in the Author’s Note that South Africa adolescents are a target audience for this well-written novel. Indeed, the reviewer did a search of South African booksellers and found that there is not a South African co-publisher that could market the book at an accessible price for South African youth. Exclusive Books, one of the largest booksellers in the country, does have copies of the U.S. edition of the book at just over $20 per copy, an inaccessible price for the average South African adolescent reader.

A review oriented to a primarily North American audience, has to be more cautionary. North American adolescent readers, particularly those who enjoy magical-realism, may well enjoy reading the well-crafted narrative. However, the author, does not mean her narrative to be perceived in this light. The narrative does present themes that will be familiar and attractive to North American adolescent readers: family dynamics, youthful angst and self-doubt, adventure, and romance. The primary issues that are poignantly and sensitively addressed for a South African audience are, I fear, inaccessible to a North American audience who will have little or no understanding of the socio-cultural and historical context that give meaning to the narrative for a South African adolescent reader. Reading the narrative, minus this contextual literacy, is likely to create or reinforce negative perceptions of South Africa and South African culture.

It is important to briefly highlight three areas of concern in this regard. First, the pervasive poverty among the high density urban dwellers represented by Imbali township adjacent to Pietermaritzburg. This depiction is certainly accurate, but it is presented in a largely ahistoric manner that may leave a North American adolescent reader, who most likely has no appreciation of apartheid’s legacy of brutal institutionalized discrimination under the guise of separate development, with the perception that the poverty depicted in the narrative is indicative of the all-too-present (in the North America media) stereotypical representation of the normative reality of urban Africa.

Secondly, is the centrality in the narrative of the related themes of xenophobia and the internecine endemic violence exemplified in the text by the taxi wars. Again, these tragic issues are very real in many of the urban townships in KwaZulu-Natal (where the story takes place) and across the nation. The narrative in no way romanticizes these acts of violence, indeed, Nkosi the heroine, takes an unambiguous stance against both the xenophobic violence and the taxi wars depicted in the narrative putting herself in great physical danger. However, to reiterate the concern expressed above, the endemic violence accurately depicted in the narrative is presented with minimal historical contextualization that would allow the North American adolescent reader to more accurately understand the realities of the ever present violence in South African townships such as Imbali.

Thirdly, and most problematic, is the central place in the narrative of traditional Zulu healing (represented by Nkosi’s identity as a sangoma—traditional healer) and of witchcraft. The author, to her strong credit, neither romanticizes nor does she exoticize the religio-healing beliefs and practices of the Zulu culture in her narrative. Indeed, she presents these beliefs and practices in a sympathetic and engaging manner. However, the author provides no introduction to or brief overview of Zulu cosmology that is absolutely necessary for the North American adolescent reader to understand and appreciate the complexity and sophistication of Zulu (as well as other African) cosmology, which in combination of the socio-economic realities of contemporary South Africa gives rise to both the positive benefits of sangoma prescribed Muthi (medicine) and the negative impact of witchcraft in contemporary South Africa. Absent this contextualization, my fear is that the North American reader will come away from the story with a negative and stereotypic “understanding” of South African cultural beliefs and practices as steeped in irrationality and superstition.

Finally, and on a more positive note, just as I have no hesitation highly recommending Under Water to a South African adolescent audience, I would provide a similar rating for use in a North American classroom where South Africa is comprehensively studied. In this situation, reading Under Water would enrich the students’ engagement with and understanding of the lived realities of contemporary South Africans.

Reviewed by John Metzler PH.D, Michigan State University

Published in Africa Access Review (July 24, 2019)

Copyright 2019 Africa Access