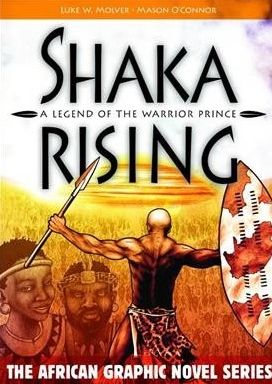

Shaka Rising, The Legend of the Warrior Prince

Shaka Rising

Shaka Rising

Young Adult Nonfiction

Story Press Africa

2018

96

A time of bloody conflict and great turmoil. The slave trade expands from the east African coast. Europeans spread inland from the south. And one young boy is destined to change the future of southern Africa. This retelling of the Shaka legend explores the rise to power of a shrewd young prince who must consolidate a new kingdom through warfare, mediation, and political alliances to defend his people against the expanding slave trade. Publisher

The graphic novels – Shaka Rising and the sequel, King Shaka – are imaginative, engaging, and innovative ways of narrating the legend of Shaka, the most renowned 19th century monarch in Southern Africa. Comic book writer-illustrator Luke Molver, a South African born in Durban, does an excellent job of telling and showing the rise of King Shaka and the Zulu nation in the wider context of individuals and groups in the region at the time. The Zulu belong to the Nguni linguistic group as do the Ndwande and Mthethwa people featured in the books. Shaka’s name is familiar to many in the West but the other major players in Shaka’s time, less so. Molver helps readers by providing images, names, and clans of historical figures at the very beginning of both graphic novels. Background notes provide useful information on history, aspects of Zulu culture, a glossary, chronology, pronunciation guide, critical thinking questions and more. Readers and teachers exploring these novels will find these additions invaluable.

In the 15th century, the Zulu were a small clan of Nguni people descended from Zulu kaMalandela, a common ancestor who founded the royal line. By the early 19th century the Zulu under Shaka dominated the northeastern areas of current day South Africa including KwaZulu-Natal. Historians often compare Shaka to European nation-builders including Napoleon, Bismark, and Garibaldi.

The first book, Shaka Rising, A Legend of the Warrior Prince opens with Shaka Zulu’s formative years. Heir apparent to his father, Senzangakona, chief of the Zulus, Shaka’s path to power is challenged by his brother. As tension builds, Shaka is forced to seek refuge with another Nguni clan. In exile Shaka builds his skills as a military leader and is soon noticed by Dingiswayo, king of the Mthethwa confederation, a collection of some 30 Nguni societies united under his rule. When Shaka’s father dies, Dingiswayo helps Shaka become chief of the Zulu. Eventually Shaka becomes the king of the Mthethwa confederacy. Shaka Rising covers this turbulent period, highlighting Shaka’s skills, his rise to power, and the defense of his people from the slave trade spreading from East Africa.

In the sequel, King Shaka, Zulu Legend Molver shows Shaka consolidating Zulu power, fending off rivals within his family and the region and confronting a new external threat from the British settling near the Port of Natal on the Indian Ocean. Perplexed when seeing Whites for the first time, Shaka eventually welcomes them seeing the opportunity to gain guns and defeat his rivals. The book ends with the murder of Shaka by his brother.

Even though both graphic novels are fictional, Molver based his series on the real history of the Zulus. The narrative is sensitive to Zulu customs and portrays the true climate of the 19th century history of the Zulu kingdom. Characterization of the people in these comic books is very appealing. The illustrations are superbly designed, colorful, and support the storyline concisely. Molver shows deep understanding of Zulu history and culture. Highlights include familial betrayals, the leadership characteristics of the Zulu kings, Zulu social structures and customs including the portrayal of the important roles of Zulu women as counselors and political devices. Shaka’s mother was his trusted advisor. His sister was married off to an opposing chief to strengthen relations, create family ties, and form alliances between chiefdoms. Both comic books, show Shaka’s leadership style as impeccable. He achieved this by initiating many cultural, political, social, and military reforms. His army’s innovative tactics allowed them to conquer other clans which strengthened their military. Shaka and other Zulu rulers also integrated spiritual leadership into their empire by consulting spiritual advisors and healers (izangoma and izinyanga). The belief system of consulting traditional healers during famine, drought, or death, are well explained. Consulting traditional healers in times of trouble is a Zulu tradition that is referenced when natural disasters such as drought, famine, sickness, or death occur. This misfortune is believed to be caused by displeased ancestors. Appeasing ancestors through various sacrifices is also shown when celebrating the death of an important person. Currently, it is estimated that 200,000 South Africans still consult traditional healers, regardless of socioeconomic status, with the hope of curing communicable (HIV/AIDS, Hep A & B, among others) and non-communicable diseases. Managing disease with traditional herbs is challenging as no clinical trials have been conducted to legitimize sangomas or healers’ medicines.

In conclusion, what we knew of Zulu history from books during my formative years in apartheid South Africa was very biased and skewed. The content of what blacks needed to know then was supported by segregated laws and controlled by the ruling party. Molver’s novels written over twenty years after the end of apartheid are a testament to the great insight and sensitivity he brings to his work. As Mbongeni Malaba, professor of English at the University of KwaZulu-Natal wrote in the Foreword to Shaka Rising, “The Graphic Novel Series aims to make great African stories accessible to a world-wide audience of young readers, drawing on multiple sources to ensure balanced and credible accounts.”

Highly Recommended

Reviewed by Fatima Barnes, EDD, MPH, MSIS, MBA, Howard University, Louis Stokes Health Sciences Library

Published in Africa Access Review (November 18, 2019)

Copyright 2019 Africa Access