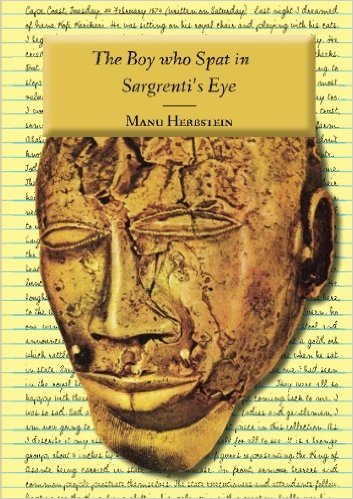

The Boy who Spat in Sargrenti’s Eye

The Boy who Spat in Sargrenti’s Eye

The Boy who Spat in Sargrenti’s Eye

Historical Fiction / Ages 12 and up

Manu Herbstein

2016. First published by Techmate in Ghana, 2014

Paperback

ISBN: 978-9988-2-3304-4

Sargrenti is the name by which Major General Sir Garnet Wolseley, KCMG (1833 – 1913) is still known in the West African state of Ghana.

Kofi Gyan, the 15-year old boy who spits in Sargrenti’s eye, is the nephew of the chief of Elmina, a town on the Atlantic coast of Ghana. On Christmas Day, 1871, Kofi’s godfather gives him a diary as a Christmas present and charges him with the task of keeping a personal record of the momentous events through which they are living. This novel is a transcription of Kofi’s diary.

Manu Herbstein’s The Boy who Spat in Sargrenti’s Eye is a masterwork of historical fiction, with the emphasis on historical. The story is set in the events leading up to the creation of the British Gold Coast Colony and Protectorate in 1874, and its main theme is a boy’s – and a nation’s — struggle to retain dignity in the midst of their loss of independence. Subtly, then, this is an anti-colonial story.

As the book begins Herbstein’s hero, 15-year old Kofi Gyan, is a boy torn between worlds in a time of great change. He is the product of a marriage between a daughter of Elmina and a son of Cape Coast, two towns at the epicenter of a conflict between the regional power Asante and the suddenly expansionist British empire. As the story begins, Britain and the Netherlands are in the process of exchanging forts in order to solidify their position on the coast. They do so without consulting any of the local African leaders, and the result is chaos leading, eventually, to a Dutch withdrawal from the coast. This sudden departure leaves Elmina and their Asante allies exposed to the power of Britain and its local partners in Cape Coast. Kofi quickly finds himself in the middle of this conflict. His paternal Uncle, Nana Kobina Gyan, the Ohin (King) of Elmina, resists the imposition of British rule and is exiled as his town burns. By contrast his maternal grandfather, Christian, is an important merchant in Cape Coast who anticipates benefits from British rule and who profits from the arrival of British troops (and journalists) on their way to invade Asante.

As the story continues, Kofi is forced to face both ways. He is recruited to assist to Melton Prior, an artist who is chronicling the invasion for the Illustrated London News, but is also convinced to act as an Asante spy. He must decide whether to collaborate or oppose the invasion, a dilemma that brings him into contact with the leader of the expedition, Sir Garnet Wolseley (or ‘Sargrenti’). Kofi gradually comes to a decision based on his observation of what British colonialism means, a theme illustrated by Herbstein in both specific incidents and overall attitudes that ring true. Wolseley and the British exhibit a casual racism, which soon grows to encompass pillage, forced labor, and brutal beatings. Their destruction culminates in the sack of the Asante capital of Kumasi. In the midst of the plunder , Herbstein contrasts two incidents – the hanging of an African bearer for taking a piece of cloth, and the theft of gold by Prior and by the British forces more generally – that decisively mark Kofi’s understanding of the rapaciousness of colonialism.

The story is fictional, of course. Kofi never existed. Nevertheless, the story as he tells it is superbly supported by evidence that the events through which he moves in the book were very real. Melton Prior’s genuine images, published in the Illustrated London News, form a centerpiece of many chapters. Other episodes are taken directly from primary sources, published accounts, and recent debates by very senior scholars. The book is, in fact, in many ways a superb bit of historical analysis. It’s also written in such a way that an individual youth reader unfamiliar with Ghanaian history could understand it without help. I think it will be most useful, however, in a high school class studying colonialism. To be sure, the contrast between brave Elmina warriors and wise Asante elders, on the one hand, and the cowardly, sycophantic Cape Coasters supporting the brutal British on the other is a bit heavy-handed. For example, the Asante King Kofi Karikari comes away as a kindly gentleman although he was also a major slave-owner. However, the fact is that at least as concerns the invaders, the dastardly deeds witnessed by Kofi in this book are very real indeed. Herbstein’s magic lies in the way that he reveals them through such a compelling story of a young man caught in the midst of turmoil and change.

Reviewed by Trevor R. Getz, Ph.D. San Francisco State University

Published in Africa Access Review (June 20, 2016)

Copyright 2016 Africa Access

I also recommend with great conviction Herbstein’s Brave Music of a Distant Drum which is an adaptation of Ama. Pairs nicely with Homegoing by Gyasi.