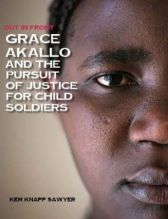

Grace Akallo and the Pursuit of Justice for Child Soldiers

Grace Akallo and the Pursuit of Justice for Child Soldiers

Grace Akallo and the Pursuit of Justice for Child Soldiers

Out in Front

Non fiction / Biography / YA

Morgan Reynolds

2015

64 pp.

ISBN: 978 1 59935 456 9

In this slim biography, Sawyer presents not only the story of Grace Akollo—stolen from her bed in the night by members of the Lord’s Resistance Army in Uganda—but also the plight of child soldiers throughout the world, both historically and in the present day.

The book begins dramatically: Grace and her classmates at St. Mary’s Catholic boarding school in Uganda are awakened by hundreds of rebels of the LRA, a militia that is led by Joseph Kony—an internationally-sought warlord seeking to overturn the government of Uganda. The girls—139 of them—are given the alternative: join the LRA as soldiers or die.

Following this brief introduction (Chapter 1), the book then shifts to describe more broadly the role of children in armed conflict (Chapter 2). For some readers, this leap from the specific story of Grace (which is left, quite without warning) to focus more broadly on the issues surrounding the abduction of children into warfare may feel like a jarring interruption; for others, it may feel a necessary move to fill the gaps and provide a backdrop against which the story of Grace (and so many other child soldiers) occurs. “Children in Armed Conflict” begins with medieval Europe and the Children’s Crusades, and traces the history of child soldiers through the American Civil War, World War II, and—more recently—the Khmer Rouge, Nepal, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Liberia, and the Middle East. Included are photographs of child soldiers in battle and quotes from their first-person accounts.

In Chapter 3, the narrative returns to Grace. Interspersed are pages of background on Uganda, the history of the British in East Africa, and the aims of Joseph Kony and the Lord’s Resistance Army; however, the bulk of this chapter tells the story of Grace’s childhood, her education, her abduction at St. Mary’s, and her subsequent role in the LRA as a child soldier and the “wife” (that is, concubine or sex slave) to a trusted Kony lieutenant “old enough to be [her] grandfather.”

Grace manages an escape in Chapter 4; however, her return home is complicated—filled with guilt and accusations. Eventually she continues her education, first in Uganda and later in the US. In the final chapter of the book, the plight of life after war not only for Grace but for child soldiers more broadly is explored—through the stories of others whose lives can never be recovered; through a description of organizations that seek to rehabilitate child soldiers and protect the rights of children, worldwide; and finally through Grace herself, who serves as an advocate against the use of children in armed conflict, and who has devoted much of her life to helping child soldiers by sharing her story with the world. “I have to use the life that I was given for a purpose,” Grace is quoted as saying. Living permanently in the US, Grace has started her own non-profit non-governmental organization called United Africans for Women and Children Rights, fighting to help former child soldiers and ensuring the rights of women to pursue education and careers.

The text handles issues of violence, rape, abuse, killing, and suicide attempts with honesty, but also with care. There is an enormous amount of information packed into these 60 pages, including numerous photographs, full-page sidebars of information, a list of sources, and a bibliography. Sawyer makes an interesting choice in how to handle referenced materials: she includes quotes in the text without attribution, making Grace’s voice (and the voices of other child soldiers) immediate and clear; only when the reader reaches the “Sources” page does it become evident that in fact the quotes are taken from elsewhere rather than directly from the speaker her or himself.

I am not entirely certain who the book’s intended audience might be; there is much material in the book that requires background understanding (geography, history, politics), some of which is provided but much of which is assumed. As well, there is a fair amount of difficult material included (coercion, abuse, physical and sexual violence). Embedding Grace’s life story within the plight—both historically and in the present day—of child soldiers throughout the world requires of readers some fairly sophisticated comprehension strategies as they follow multiple themes both within and between chapters.

In the same vein, I am also not entirely clear on the focus of the book. While it purports to be about Grace Akallo, in fact there is not much information about her included, given the book’s categorization as a “biography.” For example, despite there being photographs on nearly every spread (sometimes full-page photos, or photos that cross into both pages), there are only two photos of Grace herself: one on the table of contents, and one a side-shot of Grace at a news conference in 2006 that serves as the backdrop to the title of the final chapter of the book. (In fact, there are twice as many photos of Joseph Kony and the Lord’s Resistance Army as there are of Grace.)

Ultimately, the broad focus on child soldiers parallels Grace’s own work as an advocate against children in armed conflict; however, that intersection of themes is not apparent until the final pages of the book, and while it is a brilliant organizational strategy, it may require skills beyond those of readers who are likely to pick up a sixty-page illustrated biography.

Still, this is a timely story, and a story that Sawyer—author of several biographies for young readers—researches and tells with honesty, forthrightness, and skill. With some carefully-selected supports in place, the book can serve to call attention to the ongoing plight of children serving in armed conflict around the world. It is a topic that deserves to be engaged and understood.

Reviewed by: Laura Apol, Ph.D., Michigan State University

Published in Africa Access Review (February 24, 2016)

Copyright 2016 Africa Access