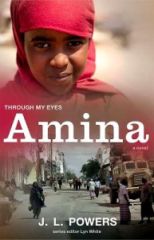

Amina

Amina

Amina

Through My Eyes

Fiction / Elementary / Middle

Allen & Unwin

2013

183 pp.

ISBN 9781743312490

Amina lives on the edges of Mogadishu. Her family's house has been damaged in Somalia's long civil war, but they continue to live there, reluctant to leave their home. Amina's world is shattered when government forces come to arrest her father because his art has been officially censored, deemed too political. Then rebel forces kidnap Amina's brother, forcing him to become a soldier in Somalia's brutal ongoing war. Although her mother and grandmother are still with her, Amina feels vulnerable and abandoned. Secretly, she begins to create her own artwork in the streets and the derelict buildings to give herself a sense of hope and to let out the burden of her heart. Her artwork explodes into Mogadishu's underground world, providing a voice for people all over the city who hope for a better, more secure future.

This is a well-researched book written for young adult readers. It is the story of a Somali teenage girl, called Amina, as she lives through a very difficult time – probably between 2006 and 2011 – during which a good part of Somalia’s capital Mogadishu was controlled by the jihadist movement Al-Shabaab. The narrative is in Amina’s voice, as is true for all books of the “Through My Eyes” series.

Amina loses two family members to Al Shabaab. First, armed men come and take away her father because Al Shabaab disapproves of his paintings and critical spirit. Then her older, soccer-loving brother Roble is kidnapped in the street. At the same time, Amina’s family cannot turn to its rich neighbors, on whose son (Keinan) Amina has a crush, because they are helping Al Shabaab in return for financial gain.

Amina is drawn to making art, like her father, but she is also drawn to creating it in public spaces, mostly in abandoned buildings, at great risk. However, as her family, now consisting of her pregnant mother, grandmother, and herself is left without any income and begins to starve, she feels compelled to give up on making art, even if only temporarily. No longer able to attend school, Amina must roam the streets to find or steal some food just to help the household survive.

Four developments eventually bring some improvement in Amina’s life and provide a conclusion to the story: she succeeds in selling one of her father’s paintings; with Keinan’s help, she manages to find a midwife so that her mother gives birth to a healthy little girl, the troops of the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) help drive Al Shabaab out of Mogadishu, and Amina begins to make art again.

Overall, the author’s representation of Amina’s thoughts and feelings about her family members and Keinan, is very persuasive, and the ways in which she depicts and provides context to the destroyed city and its resilient inhabitants are realistic and respectful.

However, this novel also has some drawbacks. First, too many aspects of Amina’s story remain unresolved. When the story concludes, peace has been largely restored and Keinan is allowed to come and visit Amina. However, the reader is left in the dark about the fates of Amina’s father and brother and about the total lack of household income that had earlier caused the family to starve. Second, why does the author have to squeeze comments about female genital cutting into the story? The suggestion that, because of this practice, Amina’s mother and grandmother take more time when using the toilet (p. 62) is puzzling; does the author really think that older women are still infibulated?

Third, the author depicts Amina and her family as in total isolation. No one calls them from in or outside Somalia; no one in the Somali diaspora sends them money or reaches out to get their news. In the period 2006-2011, in the heart of Mogadishu, this is not a realistic representation and undercuts the dynamism of the account. Fourth, although the story has many beautiful descriptions (e.g., p. 83, Amina’s prayer) and metaphors (e.g. p. 74, Amina’s anger as “a missile seeking heat”), the description of the stench and sight of Amina’s mother’s threatening miscarriage (p. 143) is too revolting for a book for young adults. Finally, while the author succeeds in presenting Amina’s collages and paintings as creative and imaginative, she renders the young girl’s verbal art as artless and dull (e.g. pp. 71, 131).

J.L. Powers is the well-respected author of two other novels for young adults (The Confessional and This Thing Called the Future), as well as a picture book (Colors of the Wind), the story of blind artist and champion runner George Mendoza. Amina is a solid book about a challenging topic and place. It deserves to be widely read and comes recommended.

Reviewed by Lidwien Kapteijns, Ph. D., Wellesley College

Published in Africa Access Review (February 28, 2016)

Copyright 2016 Africa Access