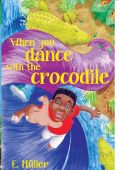

When You Dance with a Crocodile

When You Dance with a Crocodile

When You Dance with a Crocodile

Speculative Fiction, Elementary, Middle School

Wordweaver

2013

114 pp.

ISBN 9789991687841

"'Continue if you dare' flashes across the computer screen as Helena's father tests out a new computer game on her. The game is said to be extremely dangerous and Helena is warned not to touch it when her father has to leave the house. But she is cross with him for leaving her alone and in defiance goes back to the game. She clicks on a video showing a girl in trouble and, unable to resist the urge to help her, tumbles back in time to a Southern Africa beset by slave traders, wild animals, hostile inhabitants and runaway criminals. Helena's older brother Sam, intent on rescuing her, follows close on her heels. Before they find each other, their courage and resourcefulness are tested as they face and overcome dangerous and difficult situations." Publisher

Colonialism Revisited in When You Dance with the Crocodile

When You Dance with the Crocodile is a novel with a captivating blurb: “A gripping and humorous page-turner that has something of everything—science fiction, adventure, history and love.” In some respects this description fits E. Müller’s fanciful tale, especially given the author’s creation of ingeniously quirky computers. But to a much larger extent the narrative resembles works by nineteenth and twentieth-century writers who referred to Africa as “Dark Africa.” Müller amends that phrase to read “Dark Africa of long ago”—an equally pejorative label. Most of her narrative turns late nineteenth-century Africa into a hopelessly barbaric place. This matches the viewpoint of European governments that were hell-bent on dividing Africa into economically advantageous spheres of influence. Novelist Chinua Achebe analyzed the psychological side of the colonizers’ “Dark Africa” perspective: “[There is] . . . the desire—one might indeed say a need—in Western psychology to set Africa up as a foil to Europe, as a place of negations . . . in comparison with which Europe’s own state of spiritual grace will be manifest” (2). Historian Jan Nederveen Pieterse offered this quip: “Europe’s light shone brighter by virtue of the darkening of other continents” (75). In Western discourse “Dark Africa” was comparable to “Savage Africa,” and Müller utilizes the same “savage” connotation as she describes details of her “Dark Africa of long ago.”

Her novel’s blurb refers to “something of everything,” a set of categories that provide a simple structure. Müller’s “science fiction” alludes to computers producing time travel (specifically to and from the present day and the year 1889). Regarding “history,” the novelist makes use of Portuguese slave-trading and the “Caprivi Strip,” a desolate region that she ambiguously says “on paper belongs to the Germans” (68). The “Strip” harbored outlaws, one of which plays a role in the story. More importantly, Müller’s Africans of 1889 lack historically-based characterizations; they inhabit that mythically-based history that emerged largely from Western colonial sources. As for “adventure,” the book is loaded with slave-traders brandishing whips (25), swarms of killer ants (62, 73), and a Queen viewing insults as “worse than murder or thefts,” insults that deserve a death sentence (31). Finally there is “love”—a quality illustrated in magnanimous actions required by a computer game’s rules. Players are to perform compassionate acts or perish in the attempt. The novel winds down with a summation of charitable acts accomplished, but this theme is continually undercut by scenes that imagine Africa to be a continent of incredible degradation.

The alleged wrongdoing comes into focus in a string of sadistic events. Power is primarily in the hands of Paramount Chief Lewanika—the “king of a territory so vast that he himself has only a hazy notion of its boundaries” (60). Of special ferocity is the above-mentioned Queen, the Mukwai, who uses crocodiles and spears as weapons. Thirteen-year-old Sam Amadhila was threatened with death for having “insulted” the Queen when vomiting the sour milk she had forced him to drink. She plans to lure crocodiles with meat and Sam’s spear wounds will produce the blood that makes them “go crazy” (32, 40-41, 74). Later Sam is again a victim when “fierce-looking warriors . . . dragged him into the bushes” and smeared him with honey to attract an “army of thousands of ants” (62). These creatures crawl over animals and at a signal from their leader, the insect army attacks and “hundreds of small forceps [begin] tearing away at the meat of the live animal” (62). The cruelty of Paramount Chief Lewanika surfaces as we learn that he cannot tolerate the color red as the result of his bloody wartime experiences. People who display that color are “asking for the death sentence” (73). No matter how irrational this law is, execution faces those who violate, however unintentionally, that color-based taboo. Müller molds the Paramount Chief as more humane than the Queen since he presumably kills in self-defense, but the policies of both are designed to destroy innocent lives.

As the plot unfolds, Helena Amadhila (Professor Amadhila’s daughter), has used her father’s computer to whirl her through a “wormhole” (a kind of wind tunnel). She lands in 1889 and tries to save Ruth, a girl trapped in a hole made by Portuguese slave-traders. Helena becomes another Portuguese captive along with thirty to forty shackled children being prodded toward an Angolan slave market. The girls manage to escape, while Sam (in a different location) wins over the Queen with a flattering photo his pocket camera could produce in seconds. By chance Helena also has a gadget in her pocket: the latest computer game. This game is programmed so a person can speak and understand any language; so children are protected from vulgarity (a “beep” blocks obscene speech); so imitations of roaring lions can deceive people (e.g., Zakes, a felon from the Capviri Strip, is tricked by lion noises). And among other amazing things, the computer produces “heavy metal” music—sounds that are “magic” to guards who’ve been hired to prevent captives from escaping. Loud screaming accompanies their panic-driven departure.

As is common in adventure stories, nearly everyone is on the move. One of Müller’s strategies is to use each succeeding chapter as a way to rotate what all the central characters are doing. This jumpy, oscillating technique produces an illusion of heightened anxiety. Ruth is searching for her widowed mother who is in Sesheke (Chief Lewanika’s community); Helena is struggling to free Ruth from the slave chain and bring her to her mother unharmed; Sam is frantically hunting for Helena (who has mysteriously disappeared from their residence in Windhoek). Besides this group, there is Maddy, the companion of Zakes, who is trying to escape Zakes’ brutal beatings; and finally Matsimela, who wants to remain as far from the twenty-first-century as possible given the fact that he is a Windhoek “street boy” (one assigned as “test subject” for the game). He is overjoyed by life in 1889: “He had gone from pavement to paradise” (50). He is teaching English to twelve-year-old Chief Letia; speaking French to the missionary’s wife; thriving as a trader of beads for blankets, and concocting a hugely intoxicating beer (50, 83). But the game’s inventor intercepts Matsimela’s plan by kindly announcing his intention to adopt him. Thus the “street boy” joins the other present-day characters who are being swept up the wormhole to Professor Amadhila’s spacious home.

When You Dance . . . is the work of a writer who knows how to craft plotlines. But at the same time, her views of Africa reflect the colonizers’ “Dark Africa” theory, their failure to acknowledge well-documented history. And claims that explain total freedom of choice (as indicated on Müller’s copyright page) do not resolve every problem. The typical rationalization used by publishers reads, “Names, characters, businesses, places, events and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner.”

If storytellers believe they have a license for misrepresenting specific groups, what sort of questions need to be asked? Can writers for children arbitrarily annul the humanity of a selected population? The subject matter in When You Dance . . . begs this issue since the novel’s inhumane features are usually actions by assumed “savages.” Müller could have taken account of Africa’s innumerable attributes and lengthy history, but instead she morphed her tale into a colonialist throwback. She leaves unexplored the realities of Africa’s immense story. And it is young, diverse readers who are left in the dark.

Works Cited

Achebe, Chinua. Hopes and Impediments: Selected Essays. New York: Doubleday, 1989.

Pieterse, Jan Nederveen. White on Black: Images of Africa and Blacks in Western Popular Culture. New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 1992.

Reviewed by: Donnarae MacCann, University of Iowa

Published in Africa Access Review (February 28, 2014)

Copyright 2014 Africa Access

A careful reading of this work of adolescent fiction written and published in Namibia left me with considerable ambivalence. On one hand, I was positively impressed that the author placed African (Namibian) teenagers as smart, science and technology savvy problem solving adventurers. On the other hand, I was left deeply distributed by the oppositional dichotomy through which the author presents contemporary ” modern” Namibia (southern Africa) in counter distinction to southern Africa in the late 19th century.

Specifically, the plot features three contemporary Namibian teens (a brother and a sister, and a non-related male), who independent of each other, are inadvertently sucked into a time warp while playing a new computer game. The protagonists each end up in different locales in the Barotse kingdom of now western Zambia in the 1890s. Each survives through their intelligence and bravery. The real problem is in way in which the author constructs late 19th century Barotse culture and society. Throughout the narrative the Barotse–and other African peoples–are represented as belonging to “Dark Africa” (direct quote, used a number of times in the narrative), where people’ s actions are governed by deep, irrational superstitions with a strong tendency towards acts of violence–that are often fleckless. The contemporary heroes whose values and world-view are informed by “modernity” (thanks to colonialism and exposure to Christianity?) are horrified by the beliefs, values and behaviors of their recent ancestors.

It is shocking that in 2012 a work written in Namibia, by a Namibian can depict and represent African societies and cultures in such starkly negative terms. Not Recommended.