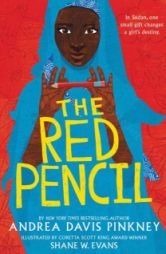

The Red Pencil

The Red Pencil

The Red Pencil

Fiction, Elementary, Middle School

Little, Brown

2014

308 pp.

"After her ...village is attacked by militants, Amira, a young Sudanese girl, must flee to safety at a refugee camp, where she finds hope and the chance to pursue an education in the form of a single red pencil and the friendship and encouragement of a wise elder" Publisher

Are ethnic cleansing and large-scale violence against civilians a topic that can be raised with readers between eight and twelve years of age? Pinkney and Evans’ The Red Pencil shows that this is indeed possible. Their brilliant rendering of the large-scale violence that took place in Sudan’s westernmost province of Darfur in the years following 2003 respects both the sensibilities of young readers and the dignity of the victims.

The story is told in the form of a series of free verse poems and pen drawings. It begins with twelve-year old Amira takes on life in her agrarian village in South Darfur in 2003, just before the violence erupts. The poems of this part of the book give the reader Amira’s perspective on her chores, her lost tooth, an overheard quarrel between grown-ups; her village’s crops, the moon; her father and mother; the birth of her physically challenged sister; the neighboring boy; the girlfriend who leaves the village to go to school in the city; a typically Sudanese haboob or dust storm; the birth of a little lamb, and the special twig with which Amira draws in the sand both what she sees around her and what she imagines. Evans’ evocative and imaginative illustrations not only represent the spirit of Amira’s own drawings but also beautifully capture the Sudanese physical environment.

Interspersed with these glimpses of life in the village are a few stark poems about war. In one such poem Amira’s father explains to her that they are living in a time of war: “Brothers are killing each other/ over the belief/ that in the Almighty’s eyes/some people are superior” (p. 21). In another her mother tells Amira about a potential attack by Janjaweed, “evil men on horseback” (p. 59). When the attack materializes (p. 110), village and fields are burned down and the survivors, including Amira and her family, have to flee. Amira’s father (Dando) is killed. As they make the long, harsh, and dangerous trek to the refugee camp of Kalma, Amira misses her father: “I pretend Dando is walking alongside me,/ holding my hand,/ helping me through this./ …. I pretend/ so, so hard,/ with my whole heart./ But it’s fruitless./ This so-hard pretending/doesn’t work./ My father’s footprints, nowhere” (p. 127-128). The first part of the book ends with this long walk to safety.

The Red Pencil’s second part describes life in the refugee camp and Amira’s long journey from traumatized silence (she stops speaking) to hope and healing. The red pencil given to her by a relief worker helps her on this journey of recovery. Whether Amira will be able to fulfill her hope of going to school remains an open question.

In the “Author’s Note” at the end of the book, Davis Pinkney gives the book’s backstory. How her travels in Africa and visits to many African schools made the violence in Darfur especially real to her; how she drew on news reports and numerous interviews with people who lived through the violence, and how the actual story of a traumatized girl in a refugee camp who gradually reconnected with the world around her after receiving a pencil and a writing tablet became her inspiration for this fictional account. “This story has been heavily vetted and factchecked,” Davis Pinkney adds (p. 312), and this extra effort, in addition to her research and creative imagination, has most definitely paid off. The result is a book that can and deserves to be read to, with, and by English-speaking readers of middle-school age everywhere.

Andrea Davis Pinkney is a highly accomplished and award-winning author, who has written many works for children and young adults, including illustrated books about aspects of African American history such as Sojourner Truth’s Step-Stomp Stride, Let it Shine: Stories of Black Women Freedom Fighters, Duke Ellington, and Boycott Blues: How Rosa Parks Inspired a Nation. Illustrator Shane W. Evans is equally accomplished and has illustrated books such as Bintou’s Braids by Sylviane Diouf; Did I Tell You I Love You Today? by Deloris Jordan and Roslyn Jordan; and Free at Last! by Doreen Rappaport.

The Red Pencil is in all aspects a remarkable achievement. It comes highly recommended.

Reviewed by Lidwien Kapteijns, (Wellesley College)

Published in Africa Access Review (January 21, 2015)

Copyright 2015 Africa Access

I agree with the reviewer that The Red Pencil is a remarkable book. The poetic format and line drawings focus on emotions and inner thoughts rather than on outward episodes, hence avoiding some of the common stereotypes associated with stories of refugees and child soldiers during civil wars. This structure also highlights the importance of writing/drawing as a means of releasing pent-up emotions and other suppressed psychological issues.

Amira’s poems give readers an insight into the emerging adolescent’s conflicting emotions: respect for traditions versus a more modern outlook, women’s dependence on traditional roles versus desire for freedom and education, respect for mother and elders versus defiantly making her own decisions, the futility of war, concept of home, etc. The most touching aspect of Amira’s emotions is her inability to speak because of the severe trauma of the war, especially her initial inability to acknowledge and accept her father’s brutal death. These themes are developed through a number of episodes and tropes that are introduced in the first part of the book, and which are subtly and cleverly pursued, and given new meanings and interpretations, in the second part — such as summoning the moon at night; the competition/war between Dando and Anwar over tomatoes and the civil war; friendship between Leila and Gamal; mother’s views on girls’ education; role of Amira’s friend Halima; writing twig and the red pencil, etc.

I highly recommend the book.