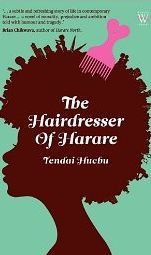

The Hairdresser of Harare

The Hairdresser of Harare

The Hairdresser of Harare

Fiction, New Adult

Weaver Press

2010

ISBN 978-1779221094

"...Vimbai is a hairdresser, the best in Mrs Khumalo's salon, and she knows she is the queen on whom they all depend. Her situation is reversed when the good-looking, smooth-talking Dumisani joins them. However, his charm and desire to please slowly erode Vimbai's rancour and when he needs somewhere to live, Vimbai becomes his landlady. So, when Dumisani needs someone to accompany him to his brother's wedding to help smooth over a family upset, Vimbai obliges. Startled to find that this smart hairdresser is the scion of one of the wealthiest families in Harare, she is equally surprised by the warmth of their welcome; and it is their subsequent generosity which appears to foster the relationship between the two young people. The ambiguity of this deepening friendship - used or embraced by Dumisani and Vimbai with different futures in mind - collapses in unexpected brutality when secrets and jealousies are exposed. Written with delightful humour and a penetrating eye, The Hairdresser of Harare is a novel that you will find hard to put down." Publisher's Note

I enjoyed this novel at a number of levels: in the context of Zimbabwean literature, there hasn’t been that much humour (apart perhaps from the short stories in Laughing Now) since Dambudzo Marechera and it’s encouraging to encounter it here. I also felt it was an interesting fit with Brian Chikwava’s Harare North (set in London) in the revealing of the more savage sides of Zim politics and social inequalities through the eyes of an unreliable narrator.

And that’s the other level — the perfectly judged ambiguity of tone rendered as an effect of point of view Vimbai starts out comically vain but keenly observant, and a lot of the early humour arises from her observations on the salon, its clients, its owner, the other hairdressers, cumulatively amounting to a microcosm of late Mugabe Zimbabwean society, with its hypocrisies, hierarchies and narcissism. The use of suspense is good too, with Vimbai’s gradually unfolding backstory explaining why she lives alone in a large suburban house, why she’s fallen out with her family, why she’s a single mother, etc. There are plenty of hints even at this stage as to her shallowness and selfishness, but she remains a likeable character with plausible motives.

After Dumi moves in with her, the plot thickens and characterisation becomes more complex as Vimbai’s relationship with him becomes more ambiguous. Because the reader knows well in advance of Vimbai that Dumi is gay, the dominant tone shifts from comic to ironic. Vimbai’s entrancement with Dumi’s much richer family and their reception of her spells out the way cronyism and corruption have permeated the society. She appears innocent, but, dazzled by luxury, is she complicit in their buying of her as cover for their son’s gayness? In the material conditions of a city where money has no value — and everyone has to hustle to survive –even if she’s aware she’s being bribed, can she be blamed?

By the time she finds out Dumi is gay, her reaction is clearly rendered as an effect of the social brainwashing which is more clearly dramatised in Harare North. In the latter the persona is one of Mugabe’s Green Bombers, and the novel is unsettling partly because he never backs down from the ideology of violence-as-control espoused by the Bombers. At the same time, he is mentally unstable and can’t be relied on as a narrator. Vimbai is similarly unreliable in the sense that, while she may suffer at the hands of the elite and is sexually abused by her daughter’s father, she fully subscribes to the leadership’s designation of gays as ‘worse than pigs and dogs’. Her reaction is an effect of the violence and corruption of Zimbabwe’s ruined economy, the way poor people take refuge in Pentecostal churches, which similarly preach homophobia, and the need for scapegoats. However, the writer’s balancing of comic and serious maintains ambiguity so effectively that even Vimbai’s betrayal of Dumi doesn’t destroy our sympathy for her. Which is quite a feat

Published in Africa Access Review (February 1, 2013)

Copyright 2013 Africa Access

Reviewed by: Jane Bryce, Professor of African Literature and Cinema, University of West Indies, Cave Hill