Wangari Maathai: The Woman Who Planted Millions of Trees

Wangari Maathai: The Woman Who Planted Millions of Trees

Wangari Maathai: The Woman Who Planted Millions of Trees

Picture book, Biography, Elementary

Charlesbridge

2015

Unpaged

ISBN 9781580896269

A picture book biography of Kenyan environmentalist and political activist Wangari Maathai.

Wangari Maathai: The Woman Who Planted Millions of Trees by Franck Prévot and Aurélia Fronty (illus.) joins the list of picture books about The Green Belt Movement and its founder, Nobel Peace Laureate Wangari Maathai. Previous titles about Maathai include Wangari’s Trees of Peace: A True Story from Africa (Winter, 2008), Planting the Trees of Kenya: The Story of Wangari Maathai (Nivola, 2008), Mama Miti: Wangari Maathai and the Trees of Kenya (Napoli, 2010), and Seeds of Change: Planting a Path to Peace (Johnson, 2010). All of the ‘Mama Miti’ authors’ celebrate Maathai’s ground-breaking concept of tree planting as a catalyst for environmental and socio-political action. Each compelling narrative shows and tells what can happen when an individual becomes an agent of change, fights for what is right, and stands firm against detractors.

Prévot provides a solid snapshot of Wangari’s early life, her lush village home, her education despite prevailing norms that kept girls at home, her study abroad, her transformation from conservationist to community organizer, and her transition from activist to Nobel Peace Prize Winner. What sets Prévot’s book apart are his frank descriptions of racism Maathai experienced in the U.S. and Kenya and the struggles blacks waged in both countries against discrimination.

For the next five years, Wangari discovers snow, forests of skyscrapers, and people who look nothing like her. Even cornfields in America are different from those at home. Wangari also discovers that even in a great, free, independent country, some places are forbidden to black people. Just like at home, some schools are for white people only. During the 1960s angry African Americans demand the same rights as white people. At the same time, in faraway Kenya, another anger turns into triumph, for more than ten years, black people have been demanding the right to cultivate their land and govern their own country. Now they achieve independence from Britain at last. (Prévot)

Prévot also exposes the hypocritical behavior of moneyed Kenyans in the post-colonial period and their collusion with international capital.

…the British colonists are no longer the masters of Kenya. The country is free, but the trees are not —they still cannot grow in peace. Kenyans are cutting down trees and selling them as the colonists did. By using the land where the trees used to grow to cultivate the tea, coffee, and tobacco sought by rich countries, they can make more money. (Prévot)

Prévot identifies Wangari’s mother as the original source of her conservationist fervor. He includes a quote from her mother that Wangari never forgets, “a tree is worth more than its wood.” He explains that Wangari combines her mother wit, academic training, and on-the-ground experience to explain the roots of rural poverty in Kenya. “Women can no longer feed their children, since plantations for rich people have replaced food-growing farms. Rivers are muddy—the soil has been washed away by rain because there are no tree roots to hold it back.” (Prévot)

Prévot champions Wangari’s commitment to change the status quo; to educate her people on the importance of planting trees; her awareness that “change happens slowly,” that the present is “harsh and difficult,” and “replacing hundreds of thousands of missing trees is expensive.” He uses words like “confident,” “determined,” and “stands tall” to characterize Wangari’s resolute spirit and her willingness to keep going undeterred by her critics, including the Kenyan president who is against her efforts. The book informs us that Wangari recruits people from all walks of life to join the Green Belt Movement. They help plant more trees, earning her the name “Mother of Trees” or as fondly called in Swahili, “Mama Miti.” My only criticism of the book is the author’s repeated use of the misleading word “tribe.” For instance: “President Moi tries to divide the people in order to rule. He knows that when tribes fight one another, the president can quietly govern the way he wants.” Substituting the word group for “tribe” in the sentence would have created a powerful understanding of the universality of divide and rule tactics.

This is a great book for all but especially for girls who have been told over and over that they can’t do what they want to do or be who they want to be for one reason or the other. The book is a testament to what determination, resilience and passion for a cause can do. It is a story with the lesson that giving up is not an option. Of particular value is the addition of a chronology of “The Life of Wangari Maathai” with captions of the historical landscape leading up to her birth and actual milestones in her life. Other additions include a caption on deforestation and the impact on the animal population, quotes from Wangari’s autobiography Unbowed, and a brief paragraph on “Kenya Today.”

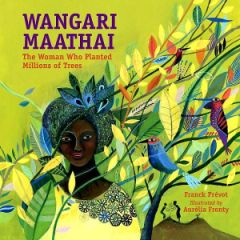

I highly recommend this book for libraries that serve elementary and middle school children and for home libraries. Young readers may require the use of a dictionary and inquisitive minds may need do additional research on some of the historical facts, but overall that is why this book is unique. It is jam-packed with research possibilities on colonialism, the environment, culture, politics, human rights, and many more. Teachers will find this a very good resource for many subjects and a starting point for more in-depth understandings of different everyday life causes. The past, the present, and the future are skillfully brought together. Wangari maybe gone, but what she started still lives on. Illustrator Aurélia Fronty’s expansive illustrations are deeply abstract but thought provoking. Beautifully crafted, each allows the reader to go beyond the few written sentences on each page.

Reviewed by: Jane Irungu, Ph.D. University of Oregon

Published in Africa Access Review (November 29, 2015)

Copyright 2015 Africa Access