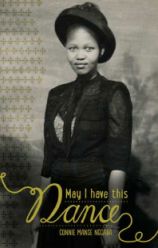

May I Have This Dance?

May I Have This Dance?

May I Have This Dance?

Biography

Cover2Cover

2015

ISBN 9780992201791

Connie Manse Ngcaba tells her story of growing up in the Eastern Cape, South Africa, where she became a nurse, community figurehead and a leading voice of dissent against the apartheid regime, culminating in her being detained for a year without trial at the age of 57.

This inspiring autobiography is the story of a remarkable, strong, and courageous woman’s love of family, community, and country. It is the story of a life lived with deep compassion for all. Completed when the author was 84 years old, this book is filled with wisdom and valuable lessons from a life lived not only in the struggles against apartheid but also, and satisfyingly, during the ultimate triumph over it. As Ngcaba explains in the foreword, “My Desire has always been that I should live a meaningful and rewarding life, pursuing knowledge, creativity and self-expression while contributing to my community and humanity in general” (page viii). She succeeded.

The foreword is followed by a touching letter addressed to her deceased husband which concludes, “Thank you, dear, for helping me reach this age, for supporting all my efforts and trusting me with what you had for all these years (x).

Ngcaba, who was born in the Eastern Cape, describes her happy childhood in a nurturing environment. In 1939, after her father’s death and after mother left to find work in Johannesburg, she was sent to live with her caring aunt. Ngcaba was brave. She did not feel abandoned. She selflessly wanted her mother to leave knowing that her daughter would cope with her emotions and the changes.

She did well in school, ending up as a nurse, first in a hospital and later at a community health clinic at Duncan Village in East London, where she lived with her family and worked in the child health and welfare section. She worked in the clinic for 32 years without promotion while less qualified white colleagues were promoted. It was the African nurses who made home visits and knew their community, but it was white nurses who made crucial decisions about which families got support. She recounts an incident when she recommended that a family get support and the white supervisor refused, saying, “They don’t look poor.” Ngcaba writes, “The injustice of it all provided fertile ground for my political consciousness to grow” (63). Ngcaba’s husband, a professional dancer also helped in the community with tennis and dancing clubs for young people.

Ngcaba joined the ANC (African National Congress) and was active in fighting injustice. She was also active through the YWCA, which organized youth activities and helped the community in many ways, including running a soup kitchen. The security police regularly terrorised community workers. She did not escape their harassment.

Ngcaba and her sons were involved in the forming of the Duncan Village Association in 1985, just a month before the government declared a state of emergency. Duncan Village did not escape the turmoil, and Ngcaba worked tirelessly to help her community. At the age of 57, she was detained without being charged, and her description of the year in detention is touching. Two of her sons were also detained at the same time. They spent two years in detention and later fled into exile. Her husband lost his job. After her release, Ngcaba continued to help her community by working with the YWCA.

Towards the end of the book, Ngcaba offers wisdom garnered from an extraordinary life lived with courage and compassion. She writes about issues including how technology affects women and balancing tradition and professionalism. Finally, she offers a practical family constitution to guide her children and others.

Ngcaba tells this story in a straightforward and charming conversational style. For example it is full of simple declarations that are true and powerful. “Life has taught me that if there is anything constant, it is change” (9). She also comments on her life after she was released from detention: “After a year in detention, I finally slept on my own bed in my own house. It was like a dream come true” (84).

South African women played an important part in the struggle against apartheid. Like the author, they often played a direct part in the struggle while keeping their families thriving. Many women like Ngcaba were imprisoned. The stories of these courageous women remain mostly untold. This has begun to change, albeit slowly, and Ngcaba’s autobiography is a welcome and important addition to the stories of these often unheralded heroines. Her story shows the sacrifices the women made and their triumph at the new dawn of democracy. Some historical context would have enriched it in places.

This is an inspiring well-written book that should find a wide audience. Recommended.

Reviewed by Lesego Malepe, Ph.D., Independent Scholar

Published in Africa Access Review (December 17, 2015)

Copyright 2015 Africa Access